A Surprise Twist in the Case of the High Profile Ancient Coin Collector in New York

The headline to this article sounds something like the name of an episode in Scooby-Doo, or one of the "Famous Five" books by Enid Blyton, however it is an accurate summary of the events of the past week in the world of ancient numismatics. I had to laugh at the way the Daily News in New York opened their article regarding the most recent development in this case: "A knuckle-headed hand doctor busted for hawking fake ancient Greek drachma must pen an expose on the dirty dealings of the coin collector world to avoid jail time."

If you've been receiving our emails for a while, you may remember a story that broke at the start of the year involving a high-profile collection of ancient coins in the US. The auction was of "The Prospero Collection, was handled by Baldwin & Sons of the UK, and made around $25m.

You may recall that the auction didn't pass entirely without incident - the vendor of "The Prospero Collection" (Dr Arnold-Peter C. Weiss) was arrested "on felony possession" of several ancient coins that were allegedly recently looted from Sicily. Dr Weiss' arrest took place just prior to the auction of the Prospero collection, and in fact involved what was one of the key items in that sale - a 4th century BC silver decadrachm from Akragas.

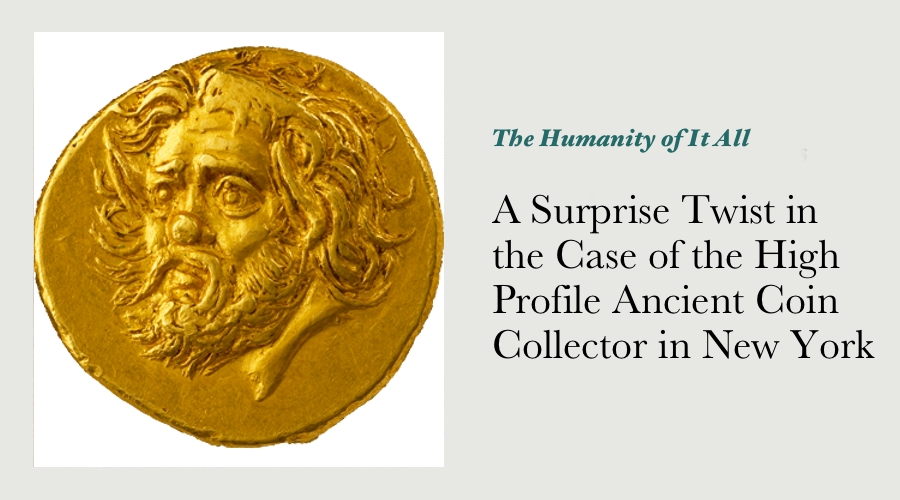

To the uninitiated, this is one of the most coveted coins in the entire world - it had a pre-sale estimate of US$2.5 million, and this was the coin expected to be the most expensive Greek coin ever sold, meaning that it was expected to be more highly prized than the gold stater from the ancient Greek city of Pantikapaion that ended up selling for US$3.25m. Another coin was also seized by authorities at the same time, a 4th century BC silver tetradrachm from the ancient Greek city of Katane, this coin was listed with a pre-sale estimate of no less than $300,000.

Dr Weiss is a rather high profile collector of ancient coins - he is a former treasurer of the American Numismatic Society, chairman of the board at Rhode Island School of Design's art museum and (until very recently) was on the collecting committee of the Harvard Art Museums. He is also a "principal" of Nomos AG - a dealer and auctioneer of ancient coins based in Switzerland.

This arrest was big news in the numismatic world for a number of reasons - there has been a movement underway for the past few years in the US for laws to be enacted (and indeed enforced) preventing the import and ownership of historical artefacts that have been illegally removed from the country in which they were discovered, and by extension, from the nation that owns them. to say that there is strong resistance to these laws from pockets of the numismatic fraternity is a gentle understatement.

The presumed consequence of a successful case against Dr Weiss was that it would send a very strong signal to ancient coin collectors worldwide as to the risks inherent in owning coins that do not have an established provenance. Although Dr Weiss has since pled guilty to three counts of attempted criminal possession of ancient coins he believed had been recently looted from Italy, the consequences are not quite as severe as they were first anticipated - the coins have since been determined to be counterfeit!

I find it to be a rather alarming development that these coins can be found to be counterfeit - not only is Dr Weiss a rather wealthy collector of ancient coins, if he isn't an expert in the area of ancient Greek coins, he is certainly regarded as being extremely experienced collector and dealer. The question then needs to be asked - how on earth could someone with a wealth of knowledge in their area of expertise, someone clearly with access to any and all resources that could be deemed as required to make an appropriate decision such as acquiring ancient coins valued in the millions of dollars, how could such a person make an incredible error in judgement as to acquire a series of counterfeit coins?

The probable answer of how I believe comes in two sections - why would they consider purchasing a suspect coin, and how could they make a technical error of authentication - the two points are separate, but linked.

The why is reasonably easy to speculate on - greed, perhaps not in the sense of the word as we regularly understand it (putting one's desire for wealth ahead of other concerns such as moral behaviour or ethics), but greed in the sense of an uncontrollable compulsion to finally own an object of desire that is just within one's reach. I have enough experience as a collector and in dealing with collectors that I can appreciate how someone might act outside their own or society's expectations of proper behaviour if they were intoxicated with the desire to own a particularly rare, historic or desirable coin. We human beings are funny creatures, and common sense certainly flies out the window many times when a collector chooses to buy something they must own.

This is where an error of authentication, grade or value can be made - when reason is set aside, perhaps due to the heat of the moment, or the illicit nature of a transaction, one's normal authentication, grading or valuing procedures can be temporarily cast aside also.

One of my own experiences that comes to mind regarding this dates to my early days at Monetarium in Sydney - a gent came into the store looking to sell a few silver crown-sized coins from the early 20th century from Italy - they weren't in particularly good condition, however when I looked them up in the ubiquitous "Standard Catalog of World Coins" by Krause Publications, one of them had an apparent market value of $3,000 - $4,000. I asked the gent what he wanted for the coins, and as I felt his asking price of $400 for the three coins was quite acceptable given the apparent circumstances, I paid him and sent him on his way.

I then took the coins upstairs to show one of my more learned colleagues - he took a brief look at them, remarked "Well, they're a few nice duds", and pitched them back at me. After forcing back the bile that had quickly jumped into my throat, I sputtered that I'd paid $400 for them. As I'd been schooled to be in the habit of asking questions if I had any uncertainty before buying anything at all, the resulting spray of profane language not only singed my eyebrows, but also stripped the paint from the walls!

The interesting aspect of this lesson for me (one that i have since paid good heed to), was that if the Italian gent had asked for $2,000, I would've had no hesitation in asking him if he would mind me having a colleague verify that the deal was going to be OK. I didn't do that as I was greedy - not only for profit, but for the kudos that comes from a colleague when a prudent decision is made! It was a lonely walk home from the office that day, but fortunately the lesson was sufficiently imprinted on my mind that I've seldom made that error again.

I suspect that the full story of the curious case of Dr Weiss is yet to emerge - if you do a brief internet search about him and this legal case, you'll see that there have been (entirely unproven) allegations that the coins were supplied by a Mafia-linked plant - a crook that passed himself off as a Sicilian villager (or an agent thereof) that had excavated the coin in recent times. Exactly what happened is of course unknown by me at this stage - this doesn't stop us from speculating as to what happened, and taking a lesson or two from it.

As the old saying goes - there but for the Grace of God go I!