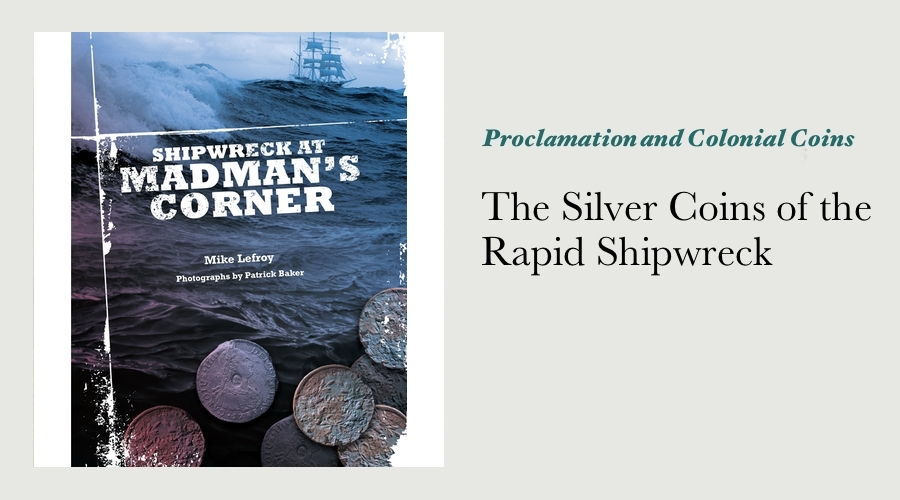

The Silver Coins of the Rapid Shipwreck

The Rapid was an early 19th-century American vessel that wrecked on Ningaloo Reef (NW WA coast) in 1811. It was bound for Canton (Guangzhou) in China, and had a cargo of 280,000 Spanish silver dollars when it sank.

Not only was this an incredible sum of money in those days (the weight of this silver was just shy of 8 tonnes), the survival story of the men on the Rapid is one of hardship and endurance. In addition to that, the discovery of the wreck in 1978 has been described as being one of the most incredible finds in Australian maritime history.

The Vessel

| Owner | Paschal Pope, William Boardman, Jonathan Amory, Ebenezer Dorr, Jonathon Dorr and Joseph Bray |

| Rig Type | American China Trader |

| Tonnage | 366 |

| Length | 31.70m |

| Breadth / Beam | 8.70m |

| Depth / Draft | 4.30m |

The Voyage

| Country of Origin | United States of America | Intended Destination | Canton (China) |

| Departure Port | Boston | Wreck Location | Point Cloates (Ningaloo Reef) |

| Departure Date | 28 September 1810 | Wreck Date | January 7th 1811 |

| Captain | Captain Henry Dorr | Description of Cargo | Silver specie, for the purchase of goods in China |

| Crew on Board | 22 | Crew Dead | 0 |

| Crew Survived | 22 | Crew Unaccounted For | 0 |

Coin Statistics

| Known On Board | 280,000 Spanish Silver Dollars |

| Unrecorded or Not Recovered | |

| Recovered From Wreck Site | "All but 19,000" (261,000) |

| Scrap / Conglomerate | |

| Held by WA Maritime Museum | 18,548 Spanish Silver Dollars |

| Legally Held In Private Hands | 151 |

The Ship

“China traders” such as the Rapid were the pride of the American fleet - they were built large, solid and fast specifically for the lucrative and competitive trade route between the USA and South East Asia.

Measuring up at 30.70 metres long and with a weight of 366 tonnes, the Rapid had three masts and no less than 8 guns. Clearly her masters took the threat to their valuable cargo very seriously.

The Rapid is, in fact, the only vessel of its type that has been studied archaeologically.

The Voyage

The Rapid left Boston for Canton on September 28th, 1810. “After rounding the Cape of Good Hope the vessel sailed across the southern Indian Ocean ‘freeway’ driven by the roaring forties. The ship then swung northeast towards the coast of New Holland, where Henry Dorr would have checked the longitude to determine how far east he had come. It looked like being a fast voyage. Disaster struck on the 101st day.”[1]

The Rapid crashed onto a reef just off Point Cloates during the night of 7 January 1811, a wild storm raged the very next day.

For most of the year, this part of the WA coast experiences south-south-easterly winds of around 25 knots, with intervals of calm weather. Between January and March, it experiences a number of cyclonic storms.

Finding that their efforts to get the ship off the reef were not succeeding and that the boat was beginning to break up, the crew of 22 took to three small boats. As they left, they set fire to the ship (as evidenced by charred wood found on the wreck site) so it would burn to the waterline and the precious cargo would be hidden from passing ships. The captain obviously planned to return and salvage the 280,000 coins, all of which he had to leave on board.

The chief officer went with 10 men in the largest boat. The second officer, with the carpenter and four sailors, took another. Finally, the captain, his clerk and three sailors took to sea in the smallest boat - one that was only 5 metres long and was leaking continuously.

As they began their journey, Captain Dorr and his companions in the small boat were so close to sinking that they had to throw overboard more than one-third of their water, their wet and heavy clothes and anything else that wasn’t essential. Even with these sacrifices, the boat had a “freeboard” of only 30 centimetres, hardly enough for such a treacherous voyage.

The survivors covered over 1,000 kilometres of open ocean with very little food and water or protection from the searing summer sun. As the wind and waves grew stronger they would have been baling continuously to keep their dangerously overloaded boat afloat.

Having survived the immediate dangers of heavy storms and high seas, they reached Christmas Island after two weeks. They found no freshwater, but were saved when it rained heavily the next day; they were able to trap a considerable amount of water in the sails. They caught large rats and land crabs, which they cooked and took with them for the next stage of their journey.

The first two boats reached the eastern end of Java, near Bali, while the smallest boat aimed for the western end near the Dutch port of Batavia (now Jakarta).

Eventually, Captain Dorr and his small boat arrived safely in Batavia after a gruelling 37 days at sea. All the crew across the three boats managed to reach Java alive, however, some were in such poor health that they died soon afterwards.

Six weeks after arriving at Batavia, Captain Dorr and some of the surviving crew were able to secure a passage back to America aboard the schooner General Green and arrived in Philadelphia on 27 July 1811.

Recovery of the Precious Cargo

It is certain that on his arrival in Boston a vessel would have been quickly organised to attempt to recover the treasure before someone else did.

Assuming that such a vessel could be manned and provisioned for departure by October 1811, a fast vessel on a direct voyage might have been able to reach the Western Australian coast by February 1812.

It is possible that some delay could have resulted from a wish to call at an Asian port en route to procure divers.

Batavia seems likely because Henry Dorr had had ample time to make preliminary arrangements during his earlier stay, So April 1812 can be considered as a likely commencement date for any salvage operations the owners of the Rapid might have performed.

Most of the coins were salvaged during the months following the wreck - the ship Meridian transported about $91,000 to Canton in 1813, more coins were held by salvagers at Madras and Java. About 19,000 were thought to have been left behind.

The Coins - Statistics and Importance

Several accounts of world trade during this period state that the practice of taking paper bills payable in London from the United States to pay for goods in Canton was not developed until the 1820s. Prior to that time, American ships did the simple thing and physically carried large quantities of Spanish silver dollars to China to pay for the cargo they wanted to buy.

Make no mistake, 280,000 silver dollars was a huge quantity of silver, even for those times. A Spanish dollar weighs about 28 grams, so the consignment of 280,000 would have weighed around 7.84 tonnes.

The coins have been described as being “clearly a consignment for the purchase of cargo.”

The dates on the coins recovered from the wreck of the Rapid range between 1759 and 1809, most of them were dated between 1802 and 1804. The most-recently dated coin confirmed that the vessel sank after 1809.

The Discovery and Identification of the Rapid Shipwreck

A group of recreational skin divers came across the wreck on July 20th, 1978. Around 600 Spanish silver coins, glass and ceramic fragments and several copper hull fastenings they had recovered from the site were handed over to the Western Australian Museum in October 1978. They had also reported seeing a large mound of silver lying exposed on the wreck site.

In order to deter looters, an expedition by WA Maritime Museum staff was immediately organised.

In February 1980, the finders, Glyn Dromey, Larry Paterson, Frank Paxman and Barry Paxman, received a reward of $17500 for their efforts. This amount was later increased to $30,000.

The story of the Rapid took until the 5th of May 1981 to uncover. Graeme Henderson travelled to Boston early in 1981 in order to conduct the research necessary to identify the vessel. While in Boston, Henderson found an article in the “Shipping Memoranda” of “The Columbian Sentinel” dated August 3rd 1811 that read: “Ship Rapid, Captain Dorr, of and from Boston, has been lost on the coast of New Holland. Captain and crew saved. Captain Dorr and part of the crew of the Rapid navigated to Philadelphia the schooner General Greene, she had lost her Captain and most of her crew at Batavia. ”

That small clue led to the identification of the mystery wreck at “Madman’s Corner” discovered by Frank Paxman and his colleagues.

A film entitled “Wreck at Madman’s Corner”, and an exhibition at the Shipwreck Galleries were prepared following the discovery and identification of the wreck.

The Historical Importance of the Rapid Shipwreck

The Rapid is a significant event in the history of maritime trading patterns during the late 18th century and early 19th century. Very little historical information exists about the activities of American trading vessels off the Western Australian coast during this period.

The Rapid is regarded as being of outstanding archaeological significance, as it is the only “American China trader” that has been studied archaeologically.

The Rapid is also extremely significant in the history of Western Australia prior to European settlement. The camp prepared by the survivors of the Rapid provides archaeological evidence of one of the few known sites of European contact with the mainland of Western Australia prior to 1829.

Footnotes:

-

Lefroy; Mike, “Shipwreck at Madman’s Corner”, WA Museum, Welshpool, 1999, p 60. ↩