WJ Taylor's Kangaroo Office & Patterns of 1855 And 1860

William Joseph Taylor was a British entrepreneur active in the numismatic manufacturing industry in London in the late 19th century.

An Entrepreneur In Every Sense Of The Word

Perhaps his largest project was the Kangaroo Office at Port Phillip between 1853 and 1857 – a venture intended to take advantage of the explosive economic growth in Australia following the discovery of gold in 1851. The pattern tokens struck by Taylor for this venture are among the most keenly sought of all Australian numismatic items. Taylor is variously described as having been an engraver; a die-sinker and a medallist.[1] He was an entrepreneur in every sense of the word – a man with an ability to dream big, he had a keen eye for an opportunity, an appetite for risk and the drive to pursue his goals.

Taylor was born in 1802 and passed away in 1885, began his apprenticeship in 1818, and established himself as a producer of medals and tokens in London in 1829.[2] Forrer’s “Biographical Dictionary of Medallists” lists several dozen medals and medallions that were engraved and struck by Taylor from the early 1800’s onwards. In 1847 Taylor produced the first copper coins for the newly independent Republic of Liberia.[3]

The Soho Mint at Birmingham (founded by Matthew Boulton) closed in 1848, and it’s plant and equipment was sold via auction in April 1850. Taylor purchased many of the Soho Mint’s hubs and dies from this auction.[4] An interesting aspect of that purchase is that these dies and hubs were consigned to the rubbish, and Taylor purchased them for their scrap metal value. Taylor used these hubs and dies to restrike many of the coins & patterns that the Soho Mint had struck between the 1790’s and the 1840’s. This re-striking activity was frowned upon by many in the British numismatic community at the time, and has undoubtedly influenced the manner in which Taylor’s other achievements have been viewed.

The Kangaroo Office – An Excellent Idea Poorly Executed

When news arrived in England in early 1852 that the miners of Victoria’s goldfields were selling their nuggets and dust at a substantial discount to the standard price of gold, it is believed that Taylor saw an opportunity to earn a profit by converting the abundant gold into small ingots or tokens that could be used in daily business. The period between when gold was discovered in May 1851 and when the Sydney Mint was established in June 1855 was a period of great uncertainty regarding the manner in which the coinage needs of the growing colonial Australian economies were to be supplied. Certain members of the British government were adamant that any gold coins struck in an Australian colony were to remain under the direct authority and control of London, whereas several less-centralised alternatives for the production of silver and copper “token” coinage were also under consideration.[5] It is also important to note that in the early 1850’s, it took 2 to 4 months for news to reach London from Australia.[6]

Taylor and two business partners financed the proposed enterprise to the sum of around £13,000, and a 600-ton clipper named the Kangaroo was purchased to transport the minting equipment to Melbourne and also continue to transport emigrants and supplies between London and Melbourne after the initial journey. The present value in 2017 of the sum invested is estimated at around £1,612,000 (A$2,642,000).[7]

The Kangaroo departed London on June 26th 1853, and arrived at Hobson’s Bay in Victoria on October 23rd 1853.[8]

On board the Kangaroo was:

- The press used by Taylor to strike commemorative medals at the Great Exhibition of London at the Crystal Palace in 1851;

- The dies that were intended to be used to strike the gold tokens;

- Copper planchets suitable for use as halfpenny tokens;

- A range of supplies acquired for resale to budding miners headed for the Victorian goldfields;

- The people required to manage the operations – Reginald Scaife and William Brown[9]; and

- Components to build a pre-fabricated shop to house the mint and to retail the supplies.

Quicker to Get from London to Melbourne than from Queen’s Wharf to Franklin Street West

Most emigrants to Victoria in the 1850’s were shocked at the state of the colony when they arrived – at that time, two to three ships were arriving each day at Port Phillip, as many as 300 ships were often anchored in the Bay at any one time.[10] In the very early days of the gold rush, many incoming passengers were dropped at Liardet’s beach, which was over a mile from the town centre.

As time passed, there was only one pier large enough for ocean-going vessels to berth at, and rather than wait for it to become available, most boats would deposit their passengers and cargo into a barge that would then unload them at Queen’s Wharf.[11] Scaife soon found that it was impossible to move his cargo from the dock into the city in one piece[12] - the wharves have been described as “a scene of dust”; with incoming freight hauled by horse & cart, wagons and even wheelbarrows from the wharves to their final destination.

These transportation methods could note cope with the weight and mass of the coining press and / or the pre-fabricated panels that would be used to construct the Kangaroo Office itself. Although there is some debate as to whether it was the press or the pre-fabricated panels that posed the transportation challenge, there is no argument that it took over half a year until the to dismantle their machinery and re-assemble it at their intended premises on Franklin Street West in May 1854.[13]

By the time the Kangaroo Office staff were in a position from which they could conduct business, unfortunately the price being paid for gold in Australia had risen significantly.[14]

The Rise in the Price of Gold Killed Their Business Model

Although some of this rise can be explained by increased competition among gold buyers in Melbourne and faster shipping between Australia and London, it was the significant shift in the balance of payments between 1853 and 1854 that saw a large number of British sovereigns arrive in Melbourne.[15] While sterling had been at an 8% discount to par in the Australian colonies at the end of 1851, these market forces saw it rise as high as 5% over par in April and May of 1854. The rapid increase in the money supply, specifically the injection of numerous British sovereigns, ensured that miners could more readily sell their gold much closer to the official price of £4 per ounce.[16] The primary competitive advantage that Taylor had anticipated his Kangaroo Office would enjoy was thus wiped out in several months, before a penny in profit could be earned.

A Glut of Supplies Killed Their Supplementary Income

An added blow to the aspirations of the Kangaroo Office was a surge in the amount of supplies being offered for sale to miners. As the population of Victoria grew between 1851 and 1853, imports for all manner of goods were paid for with the spoils of the gold rush. Food, clothing, mining equipment and building materials were just some of the goods pouring into Port Phillip Bay following the population explosion of Victoria’s gold rushes. As had happened in California several years earlier, the amount of goods arriving in Victoria during 1853 & 1854 (much of it sent out from London on consignment in the expectation of lavish profits) exceeded demand, and a glut of supplies occurred.[17]

Copper Tradesman’s Tokens - Struck Between May and September 1854

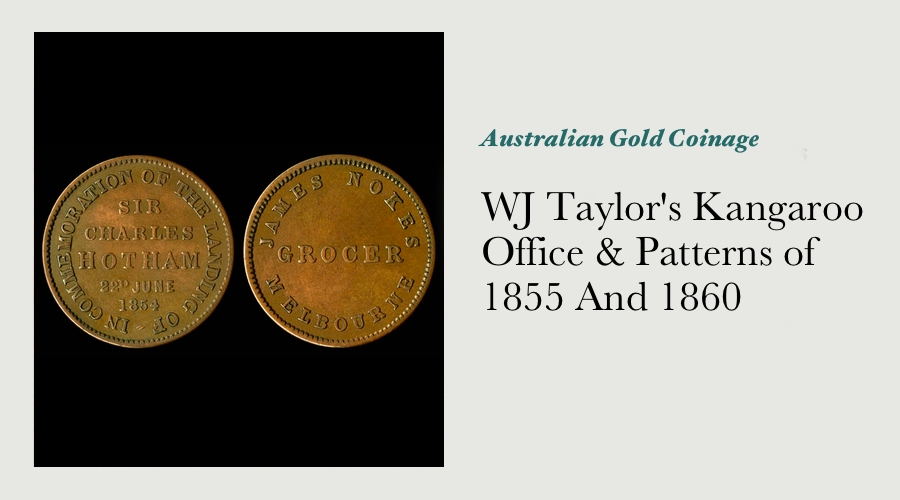

It is known that Reginald Scaife struck a range of copper tokens for a small number of Australian merchants in the time between the establishment of the coining press at Franklin Street West between May and September 1854.

Scaife struck halfpenny tokens for Crombie, Clapperton and Findlay, Nokes, Thomas, Adamson Watts McKechnie, and Thrale and Cross, as well as halfpenny tokens bearing the Kangaroo and Australia stock designs all prior to September 1854. On the back of these orders, Scaife advised his contacts in London that although it would be cheaper to produce the tokens in London and have them shipped to Australia, the convenience of having them struck in Melbourne promptly after the order was placed was appealing to potential customers.[18]

Scaife advised that there was more business to be had striking copper tokens, however he was limited to the number of copper planchets that were brought out from London. Despite the massive setback that the change in the prevailing gold price had upon Taylor’s plans, and in an effort to generate sales of some products manufactured using the Kangaroo Office press, Scaife and Brown attended the 1854 Melbourne Exhibition, held between [October and November 1854].[19]

On display was the coining press, as well as a complete set of the four gold pattern tokens from 1853. Advertisements in the local print media of the day are firm evidence that these gold tokens were offered for sale to all and sundry as “mementoes”.

The Gold Tokens of the Kangaroo Office

| Denomination | Diameter | Weight | Thickness | Obverse Design | Reverse Design |

| Two Ounce | 35mm | Kangaroo standing above date, knurled border | Denomination within raised knurled border | ||

| One Ounce | 28mm | Kangaroo standing above date, knurled border | Denomination within raised knurled border | ||

| Half Ounce | 22mm | 15.55g | Kangaroo standing above date, knurled border | Denomination within raised knurled border | |

| Quarter Ounce | 18mm | 7.79g | Kangaroo standing above date, knurled border | Denomination within raised knurled border |

Medals and Medallions

While at the Melbourne Exhibition, Scaife and Brown also struck and sold souvenir medallions commemorating the exhibition in a range of metals – white metal, silver and copper. Once the Exhibition was finished, Scaife and Taylor’s attention then turned to conceiving alternative uses for the Kangaroo Office equipment.

Taylor’s Australian Copper Patterns – 1854 to 1857

It says much for Taylor’s perseverance that following the realization in late 1854 that the Kangaroo Office would not succeed as a going concern producing gold token coinage, that he began to prepare dies for a second series of pattern copper tokens that it was hoped could be produced in Melbourne by the Kangaroo Office for circulation within Australia. The physical characteristics of these copper tokens are:

| Denomination | Diameter | Weight | Thickness | Obverse Design | Reverse Design |

| Fourpence | 34mm | ||||

| Twopence | 28mm | Broad and raised reverse rim, trellised reverse background. | |||

| Twopence | 22mm | Narrow reverse rim |

Research by John Sharples gives a strong indication that Taylor struck the first of these patterns upon receipt of a fairly direct request via a letter from the manager of the Kangaroo Office, Reginald Scaife in September 1854. Scaife mentioned in his letter that “I have written to a Sydney man abt. Making copper I.O.U.’s for 2d., 3d or 4d….”[20] Although Taylor’s copper twopence and fourpence patterns are undated, the timing of Scaife’s letter, the designs the copper tokens feature and the characteristics they share with the gold patterns of the Kangaroo Office are further evidence that they were struck around 1854.

There is little doubt that while Taylor was striking these patterns, Scaife would have made further effort to gain a contract from a number of Australian merchants and tradesmen for their production. The fact that they did not enter commercial production, and further that the dies were not shipped to Australia is firm evidence that Scaife was wholly unsuccessful in soliciting orders for these copper tokens.

Taylor’s Australian Silver Token Coinage Patterns – 1855 to 1857

It is understood that from around 1855, Taylor also began to strike shilling and sixpence patterns. Examples of these denominations have been variously recorded in gold; silver; copper; pewter; aluminium and silver-plated tin, all with milled edges. The characteristics of these tokens are:

| Denomination | Diameter | Weight | Thickness | Obverse Design | Reverse Design |

| Shilling | 22mm | 5.23g | Coronet bust of Victoria to left within knurled border | Denomination within raised knurled border | |

| Sixpence | 19mm | 2.91g | 1.40mm | Coronet bust of Victoria to left within knurled border | Denomination within raised knurled border |

It is no coincidence at all that these silver patterns also share a number of design characteristics with the gold Kangaroo Office tokens that is a raised flat rim with a knurled pattern on either side, and a straight milled edge. All of these characteristics indicate that their date of manufacture to the period between the demise of the Kangaroo Office in late 1854, and its closure in 1857.

While the obverse of the Kangaroo Office gold patterns feature a standing kangaroo over the date in exergue, the obverse of the 1855 patterns feature a coronate bust of Queen Victoria facing left. Although it is not known who engraved the portrait for the obverse, there is every indication that this design was the work of WJ Taylor himself. Dr Walter Roth was a senior member of the Australian Numismatic Society in the late 1890’s, while on a trip to England in 1892, he made a range of enquiries about the circumstances surrounding Taylor’s Australian silver patterns.

Taylor had already passed away, and “his successors were unable to state anything more definitely concerning the date and object of the issue than that they were struck in gold, silver and copper somewhere about 1855 or a little later.[21]”

Pattern coins or tokens are not struck entirely without purpose – even a manufacturer as profligate as Taylor had some commercial aim behind every item that he chose to produce. Despite this logic, the efforts that Taylor went to in order to obtain commercial orders for his Australian silver patterns are not yet known. Whatever his efforts were, the dies for the Australian patterns Taylor struck circa 1855 never entered commercial production, and certainly the dies were not even sent to Australia.

The few examples of these pattern tokens that remain in existence are testament to Taylor’s persistence in finding some means of profiting from the great Australian gold rushes of the 1850’s.

It would appear that after all possibilities that the production of gold, silver and copper token production had been exhausted by Scaife and Taylor, and as no further commercial uses for the machinery could be conceived by 1857, Taylor and his partners in London finally chose to cut their losses and close the Kangaroo Office.

“The whole affair collapsed, and instructions having been received from the promoters in London to sell all up, the managers attempted to realize whatever they could. Already over £13,000 had been invested in the ship and stores concerned. Mr Scaife, the Senior Manager, sent a whole lot of machinery and dies home – the remainder, together with the press he sold through Lloyd, his agent to Stokes (Martin & Stokes) of Melbourne, where it is being used up to this present day.[22]”

Restrikes Of Taylor’s Australian Gold, Silver and Copper Patterns – 1860 to 1890’s

There are persistent but entirely unsubstantiated statements in numismatic literature that the Port Phillip pattern shillings and sixpences struck with a plain edge were produced after the original production period of between 1855 and the mid 1860’s. These coins were certainly struck, however there is no firm published information that dates them after 1860. As an example, Andrews states that “Since that time [1853 – 1855] one or more restrikes have been issued …. having plain edges”[23], and although this is consistently reported in other numismatic texts covering this period, no empirical evidence has ever been presented to confirm this position.

Two authors that have discussed the date from which Taylor is thought to have begun re-striking coins and tokens are Walter Breen and C. Wilson Peck. Breen states that the date from which Taylor began restriking the “Backdated” 1783 Birmingham Token Cents featuring the portrait of George Washington was “…1850 for restrikes with plain edges, 1860 for those with ornamented edges.[24]” C. Wilson Peck states that “The old and cherished belief that a plain edge usually pointed to restriking is quite untenable…”

Despite this uncertainty, numismatic evidence suggests that if the plain-edge patterns are indeed restrikes, then some at least may have been struck upon the direct request of the pre-eminent British collector John Gloag Murdoch. John G Murdoch was a wealthy British industrialist whose “collection of English coins ranks as one of the most important ever formed or sold.[25]”

Murdoch’s collection also included a “brilliant and unrivalled” series of gold proof and pattern coins struck for Britain’s colonies, including a range for Australia. It is known that a number of proof and pattern coins were struck by the Australian branches of the Royal Mint and sent to Murdoch for inclusion in his collection, often struck on planchets supplied by Murdoch himself. In fact, it is believed that certain items such as the pattern 1887 Melbourne Half Sovereign struck in platinum would not exist were it not for Murdoch’s persistent requests.

It is possible that Murdoch was so taken by the story of the Kangaroo Office and Taylor’s efforts at introducing a silver token coinage in Australia that in the absence of any of the original items being available to him to add to his collection, he requested that representative examples be struck for him. As William Joseph Taylor had passed away in 1885, and as Forrer states that Theophilus left the family business in 1892,[26] these facts indicate that if a modest number Kangaroo Office shillings and sixpences were struck with a plain edge in various metals for John G Murdoch, that order would have been carried out by Herbert Taylor.

The pattern & proof gold coins struck by the Australian branch mints upon the direct request of Murdoch have been eagerly sought by collectors ever since they were first offered for sale in 1903, and there is no reason why the Port Phillip silver patterns struck for Murdoch (Montagu and Whetmore) should not receive the same recognition.

Taylor’s Australian Silver Patterns With Wiener – 1860 to 1864

In the short period following 1860, at a time well after the Kangaroo Office had closed, the equipment had been sold off and the staff had returned to England, the reverse of Taylor’s Australian pattern shilling tokens was re-deployed with several different obverse designs engraved by a Belgian medallist that had commenced work for Taylor. The 1860 Australian pattern shillings are variously reported to having been produced in gold, silver and copper.

There are three types of these pattern tokens known:

1. Head of Victoria with jewelled coronet, the designer’s initials “C.W.” incuse on truncation;

2. Head of Victoria with jewelled coronet, the truncation plain;

3. Head of Victoria wreathed with rose, shamrock & thistle.

Charles Wiener (1832–1888) was a Belgian sculptor and engraver, from a well-known European family of engravers.

Wiener began his studies as a medallist at the Brussels Fine Art Academy in 1844, and completed them in 1852. Following his graduation he moved to Paris, and worked under the famed French sculptor and medallist Eugene Andre Oudine until 1856. Wiener then settled at The Hague (in the Netherlands), and then relocated again to London in 1860. While in London, Wiener is known to have worked with WJ Taylor. At some stage in his time in London, Wiener “obtained an appointment of Assistant Engraver at the Royal Mint”.

Wiener was appointed Chief-engraver of the Portuguese coins at Lisbon in 1864, and finally returned to Brussels in 1867, after which he apparently dedicated the majority of his time to the production of medals. Charles Wiener died in Brussels on August 15th, 1888 at the age of 57. The Belgian State Medal Cabinet apparently contains a British pattern sovereign dated 1863 engraved by Wiener, as well as several models of this obverse struck in other metals.

It is believed that during Wiener’s during time in London that he came to execute work for Taylor, presumably engraving patterns for a range of projects. The JG Murdoch collection, sold by Sotheby Wilkinson & Hodge in London between March 15th and 19th 1904, contained an extensive range of English patterns in gold of most denominations, including nine patterns engraved by Charles Wiener and struck by William Taylor. They were purchased by a watch maker by the name of Mr. Evan Roberts and remained in his family for over one hundred years.[27]

These coins re-surfaced on April 18th 2008, at a small auction room in Plymouth (UK). It created quite a stir within the UK numismatic community and was reported in the June 2008 edition of Coin News magazine.[28] The Plymouth auction included six pattern British half florins and three pattern shillings, all struck in gold.

There were two different reverse designs used on the half florins, and one reverse design for the shillings. Three different obverse designs were used across both denominations, these correspond with those engraved by Wiener for Taylor’s Kangaroo Office patterns:

1. Coronet bust of Victoria, VICTORIA DEI GRATIA legend;

2. Coronet bust of Victoria, VICTORIA REGINA legend;

3. Wreath bust of Victoria, VICTORIA DEI GRATIA legend.

The first three half florins featured a reverse with the date depicted in numerals, the second three half-florins featured a reverse with the date depicted in Roman numerals. The reverses of the shillings were undated, but were attributed by the auctioneer as having the date of 1865.[29] The series of undated pattern British shillings struck by Taylor in silver, each with a plain edge and the three busts of Victoria engraved by Wiener, are attributed by the British numismatists Seaby, Rayner & Reeds to between 1863 and 1865.[30]

These pattern shillings have been described by the American auctioneers Goldberg & Goldberg as being “One of a delightful series of the 1860s and 1870s, experiments all, showing off engraving talents.[31]” This pattern of production was also followed by Taylor in relation to the Washington Draped Bust copper tokens of the United States – proofs, as well as several restrike varieties in gold; silver; copper; aluminium; gilt and pewter have been recorded.

Minor variants and several muled Washington Draped Bust copper tokens are known to have been struck by Taylor between 1862 and 1880.[32] As the Kangaroo Office pattern shillings have been regularly (informally) attributed to 1860, that is the date from which Wiener first arrived in London, these patterns obviously pre-date Weiner’s work with Taylor on the shilling and half-florin patterns of Great Britain.

Whether or not the production of these patterns coincided with Taylor’s attendance at the London International Exposition of 1862, and relate to the development of a silver token coinage for the Australian colonies remains under investigation.

Regardless, these patterns may have been used by both men to gain the attention of potential customers not only for Wiener’s engraving talents, but also for Taylor’s ability to produce medals, tokens or possibly even coinage related to Victoria’s Silver Jubilee in 1862. It is also possible that it was after these patterns were sighted, Wiener obtained his appointment to the Royal Mint.

Following the conclusion of this exercise with Wiener, it appears that the majority of Taylor’s business from this point until his death in 1885 was in the production of commemorative medals for British clients.

Although Taylor's re-striking activities have not helped perceptions of his legacy, his pioneering contribution to Australia's numismatic heritage is undeniable. It is best expressed by Dr Walter Roth, who in 1895 stated that the patterns of the Kangaroo Office were ""the most noteworthy"" relics of Australasian economic history.

-

Forrer; Leonard, “Biographical Dictionary of Medallists”, Spink and Son, London, 1916, p 42. ↩

-

Ibid., p42 ↩

-

Peck; C.W., “English Copper, Tin and Bronze Coins in the British Museum 1558 - 1958”, The Trustees of the British Museum, London, 1970, p221. ↩

-

Breen; Walter, “Complete Encyclopaedia of US and Colonial Coins”, Doubleday, New York, 1988, p 134. ↩

-

Butlin; Sydney James, “The Australian Monetary System (1851 - 1914)”, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney, 1986, p48. ↩

-

Chichester; Francis, “Along The Clipper Way”, Univ. London Press, London, 1966, p 15. ↩

-

http://inflation.stephenmorley.org ↩

-

Sharples; John, “A catalogue of the trade tokens of Victoria 1848 to 1862” in the Journal of the NAA , 7, 1993, p 32 ↩

-

Sharples; John, “The Kangaroo Office - A 19th Century Sting” in the Journal of the NAA, Volume 4 Number 7, 1988, p 29 ↩

-

Davison; Graeme, “Gold-Rush Melbourne” in “Gold - Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia”, National Museum of Australia, 2001, p 54. ↩

-

Ibid., p54 ↩

-

Andrews, Arthur. Australasian Tokens and Coins: A Handbook. Trustees of the Mitchell Library, Sydney, 1921, p124. ↩

-

Ibid, p124. ↩

-

Butlin; Sydney James, “The Australian Monetary System (1851 - 1914)”, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney, 1986, p52. ↩

-

Ibid., p43. ↩

-

Ibid. p53. ↩

-

Op. Cit., Davison, p56. ↩

-

Sharples; John, “Gold & Entrepreneurial Culture” in “A World Turned Upside Down”, Australian National University, 2001, p 182. ↩

-

http://guides.slv.vic.gov.au/interexhib/1854to55 ↩

-

Op. Cit., “Gold & Entrepreneurial Culture” in “A World Turned Upside Down”, p182. ↩

-

A Numismatic History of Australia. (1895, July 27). The Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 - 1939), p. 171. ↩

-

Op. Cit. Andrews, p124 ↩

-

Ibid, p127. ↩

-

Breen; Walter, “Complete Encyclopaedia of US and Colonial Coins”, Doubleday, New York, 1988, p134. ↩

-

Stewartby; Lord, “John Gloag Murdoch, 1830–1902”, British Numismatic Society, London, 2003, p 186. ↩

-

Forrer; Leonard, “Biographical Dictionary of Medallists”, Spink and Son, London, 1916, p 42. ↩

-

Andrew; John, “Market Scene” in the Coin News, Volume 45, No 6, June 2008, p 29. ↩

-

Andrew; John, “Market Scene” in the Coin News, Volume 45, No 6, June 2008, p 29. ↩

-

http://www.plymouthauctions.co.uk/search.php ↩

-

Seaby and Rayner; , “English Silver Coinage”, Seaby’s Numismatic Publications, London, 1974, p 153. ↩

-

http://64.60.141.198/cgi-bin/chap_auc.php?site=1&lang=1&sale=31&chapter=62&page=1%20 ↩

-

Breen; Walter, “Complete Encyclopaedia of US and Colonial Coins”, Doubleday, New York, 1988 ↩