The Silver Coins of the Gilt Dragon Shipwreck

The Gilt Dragon was a “jacht” of the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.) that wrecked off the coast of Western Australia in 1656. Not only was this just the 25th European vessel recorded to have reached the shores of the Australian continent, it was only the second to land with a known quantity of silver coins on board.

The Gilt Dragon stands apart from all other wrecks in Australia as being the “first modern discovery of an outward-bound seventeenth century Dutch East Indiaman[1].” Although the wreck of the Gilt Dragon has been studied in detail since 1963, the mystery surrounding it’s survivors remains as strong as ever.

Vessel

|

Owner |

V.O.C. |

|

Rig Type |

Jacht |

|

Tonnage |

260 tonnes |

|

Length |

41.80m |

|

Breadth / Beam |

9.80m |

|

Depth / Draft |

4.10m |

Voyage

|

Country of Origin |

Netherlands |

Intended Destination |

Batavia (Indonesia) |

|

Departure Port |

Texel (Netherlands) |

Wreck Location |

5.6 kilometres west of Moore River area (WA) |

|

Departure Date |

October 4th 1655 |

Wreck Date |

28 April 1656 |

|

Captain |

Pieter Albertszoon |

Description of Cargo |

Silver coins and cargo for trade |

|

Crew on Board |

193 |

Crew Dead |

118 |

|

Crew Survived |

7 |

Crew Unaccounted For |

68 |

Identification

|

Location Date |

14 April 1963 |

|

Primary Finders |

Graeme Henderson, Alan Henderson, John Cowen and Alan Robinson |

Coin Statistics

|

Known On Board |

40,000 |

|

Unrecorded or Not Recovered |

20,900 |

|

Recovered From Wreck Site |

19,100 |

|

Scrap / Conglomerate |

8,308 |

|

Held by WA Maritime Museum |

6,504 |

|

Legally Held In Private Hands |

4,288 (10.72%) |

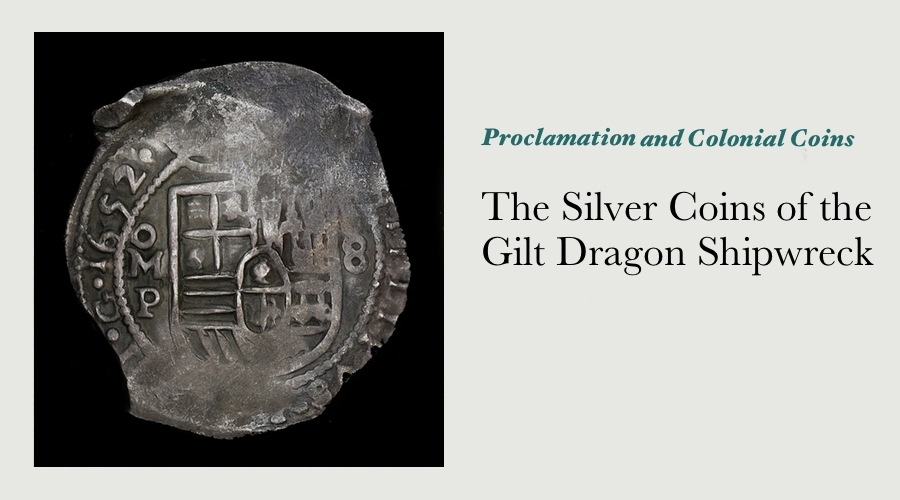

At the time the Gilt Dragon sank, it was carrying eight chests of silver coins, intended to fund the purchase of spices from Batavia (now Jakarta in Indonesia). Research by the maritime archeologist Jeremy Green indicated that this equated to “…about 40,000 individual coins.[2]”

When the Dutch authorities in Batavia learned of the wreck, several attempts were made to secure the eight chests of treasure, however the search parties were not able to sight the wreck, let alone any of the survivors or the treasure.

The wreck of the Gilt Dragon lived on in local legend across West Australia however, yet remained undisturbed for more than three centuries, and only came to light in 1963, when several recreational spear-fishermen stumbled upon it.

The story of the period shortly following the discovery of the wreck of the Gilt Dragon is nearly as captivating as the story of the wreck itself - controversy, dynamite, bureacracy, treasure, and sadly even suicide all feature in the Gilt Dragon’s story.

The Coins Recovered from the Gilt Dragon

While it is widely accepted that the Gilt Dragon was carrying 40,000 silver coins when it wrecked, research by Jeremy Green indicates that “there are over 20,000 coins still unaccounted for[3]”, and further that “A major proportion of [the coins that have been recovered] are badly corroded.[4]”

Of the approximately 20,000 coins that have been recovered, just 4,288 have been identified and are legally held in private hands.

Analysis of the 4,288 coins that have been identified and are legally held in private hands yields the following information:

These statistics clearly show that the most readily available coin from the wreck of the Gilt Dragon is a Spanish colonial 8 reals struck at the Mexico City Mint in Mexico. The coins recovered from the wreck of the Gilt Dragon that offer the best combination of rarity, size and visual appeal are arguably the silver 8 reals struck at the Segovia Mint - just 20 of them are known in private hands, they are the largest of the very few “milled” coins included within the wreck’s treasure.

Historical and Numismatic Importance

The discovery of the Vergulde Draeck was the catalyst for the development of maritime archaeology in Western Australia.

Although the wreck of the Gilt Dragon has been studied in detail since 1963, the mystery surrounding it’s survivors remains as strong as ever.

It is widely known that 118 of the 193 crew drowned when the ship sank on Half Moon Reef, and further that a search party of 7 men set out for help from Batavia. Nothing is yet known however of what happened to the 68 survivors that stayed behind. Just how such a large number of people could effectively just disappear is a mystery that many people say requires an answer.