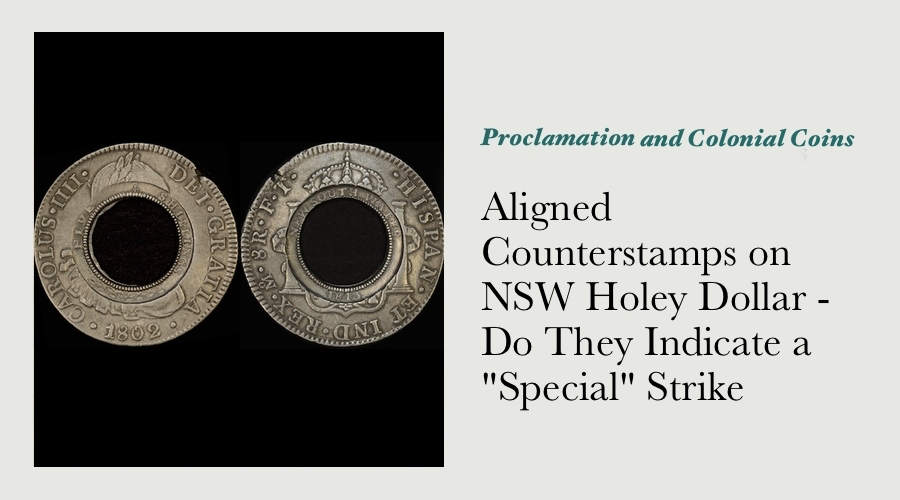

Aligned Counterstamps on a NSW Holey Dollar - Do They Indicate a "Special" Strike?

A number of times over the past four decades, several Holey Dollars have been described by a range of dealers and auctioneers as having been “specially” struck - that is, for archival or presentation purposes.

One characteristic shared by each of these coins were counterstamps that were struck in alignment with the design on the host coin.

Very few Holey Dollars have this characteristic, where if the top of the king’s head or the top of the pillars on the obverse and the peak of the crown on the reverse are positioned to sit at 12 o’clock, then the words “FIVE SHILLINGS” and “NEW SOUTH WALES” in the counterstamps run evenly across the top of the inner circle from approximately 9 o’clock to 3 o’clock.

Although past studies of the Holey Dollars of New South Wales have catalogued numerous technical aspects of each Holey Dollar known in great detail, statistics summarizing the position of each counterstamp relative to the design of the host coin upon which it was struck haven’t yet been collated, studied or published.

If it is indeed correct that a Holey Dollar featuring counterstamps aligned with the designs of the host coin was actually struck for archival or presentation purposes, having sufficient research to verify that supposition really is quite important.

In the absence of any published information being available, I’ve started doing some research to either prove or disprove this theory.

This article presents the statistics I’ve accumulated covering the alignment of the counterstamps on known Holey Dollars, and puts forward a few conclusions I believe are likely, once those statistics are taken into consideration. I don’t presume to have all the answers yet, and hope that this article starts some meaningful discussion on the subject, and adds to the body of knowledge of the first coins struck on Australian soil.

Historic and Desirable Holey Dollars Featuring Upright Counterstamps

My first avenue of research in proving or disproving this theory was to identify each of those Holey Dollars that have been previously described as having been “specially” struck. The following coins are on that list.

The Montagu / Garrett Holey Dollar (1788/3):

One of the most desirable of all known Holey Dollars is the Montagu / Garrett coin - struck in 1788 at the Mexico City Mint, with the portrait of King Charles III. Mira and Noble have recorded the counterstamps as being I/9, and B/10 - they are extremely well aligned. The historical date of the Montagu / Garrett host coin, coupled with the near perfect alignment of the counterstamps and the impeccable condition it has been preserved in, has led to speculation as to whether it was specially struck before being presented to a dignitary in colonial NSW, then preserved for posterity.[1]

The West / Baldwin / Worth Holey Dollar (1792/6):

The desirability of the upright positioning of the counterstamps is further seen in the description of lot 1039 in Noble Numismatics Auction 24b, the West / Baldwin / Worth Holey Dollar struck in 1789 at the Mexico City Mint, with the portrait of King Charles III. The Paul Worth collection of Holey Dollars was described as being “…the best private collection known…”, one that included some of the finest and rarest Holey Dollars…”[2] Mira and Noble have recorded the counterstamps of this coin as being I/10, and B/11. The auction description states “…well struck with the countermarks in the most desirable upright position relative to the original coin….[3]”

The Scottish Family / Ahbe Holey Dollar (1792/2):

Another Holey Dollar that Mira and Noble make comment on regarding the position of the counterstamps is the coin that has an enigmatic (albeit unattributed) provenance originating from a “Scottish family” (possibly from Governor Macquarie).[4]

This coin was struck in 1792 at the Mexico City Mint, with the portrait of King Charles IIII. It is clear that Mira and Noble took the careful positioning of the counterstamps to be an indication of care and attention paid during the production of this coin, the further implication being that this care and attention increases the likelihood that the “Scottish family” from which the coin apparently originated was that of Macquarie.

The Macquarie Tower Holey Dollar (1798/12):

Another Holey Dollar with upright counterstamps to have drawn comment from Mira and Noble is an example currently held in the National Maritime Museum.[5]

This coin was struck in 1792 at the Mexico City Mint, with the portrait of King Charles IIII. Mira and Noble have recorded the counterstamps as being I/10, and B/9. Governor Macquarie’s personal journal records that he laid the foundation stone for the first lighthouse at South Head on July 11th 1816.[6] An article in the Sydney Morning Herald dated August 13th 1982, states that “Governor Macquarie placed [a] holey dollar under the first light house on South Head when he laid the foundation stone on July 11 1816”[7], and further that the Holey Dollar “…owned by Governor Lachlan Macquarie”[8] was recovered from underneath the foundation stone “…when the first lighthouse was demolished in 1932.[9]”

In an article written for the Commonwealth Department of Motor Transport, Bill Mira pointed to “…knowledge that [these coins] were the personal possessions of Lachlan Macquarie.[10]” As the governor named the lighthouse “Macquarie Tower”, and intended it to be a symbol of “…an emerging, thriving colony … an icon of the British presence in New Holland…”[11] , it is reasonable to presume that Macquarie took some care in selecting the coin. If this is indeed the case, it illustrates the technical characteristics that appealed to the man that was the driving force behind the production of the Holey Dollar.

The Heuzenroder Holey Dollar (1804/12):

A Holey Dollar with upright counterstamps that has a notable provenance, but is not in private hands, is the coin formerly in the collection of H. Heuzenroder, and now held by the Art Gallery of South Australia. This coin was struck in 1804 at the Potosi Mint, and features the portrait of King Charles IIII. Mira and Noble have recorded the counterstamps as being A/9, and I/10.

Heinrich Heuzenroeder was a pharmacist in Adelaide, and had a collection of over eleven thousand coins and tokens. He has been described as being “The leading light in the South Australian numismatic fraternity …”[12] in the late 1800’s. Following Heinrich’s passing, the Heuzenroder collection was purchased by the mining magnate and philanthropist William Austin Horn. Horn in turn donated the Heuzenroder collection to the Art Gallery of South Australia in 1890.

The Roth Family Holey Dollar (1802/9):

The final Holey Dollar to have drawn comment from Mira and Noble is that owned by two important numismatists, both members of the same family (Roth). This Holey Dollar is presently believed to have been purchased by Walter Edmund Roth prior to 1893, and that it was then gifted or in some way transferred to his brother Bernard Matthias Simon Roth. Walter Roth’s collection of Australian tradesman’s tokens was purchased by David Mitchell, and then formed the basis of the numismatic collection held by the Mitchell Library in the State Library of New South Wales.

The preface to “Australasian Tokens & Coins” by Dr Arthur Andrews acknowledges the contribution Roth’s research into Australian tokens made. Bernard Roth was Vice-President of the British Numismatic Society (BNS) and of the Royal Numismatic Society. The obituary for Bernard Roth in the British Numismatic Society Journal stated that “…he was one of the leading collectors of the day”[13], and further that he “…assisted in the formation the Society.”

Why Are Aligned Counterstamps Considered Ideal?

It is interesting to consider why symmetrical placement of the counterstamps might be considered to be optimal or ideal.

The answer most likely lies in the sub-conscious or unconscious preference for symmetry that all human beings share.

Evolutionary biologists have asserted that one reason explaining a universal preference for symmetry is that parasitic infestation (a condition that affects fertility) often produces lopsided, asymmetrical growth and development. Parasitic infestation adversely affects fertility, and human beings therefore have developed an evolved preference for symmetry in the appearance of potential mates.[14]

Symmetry is also thought to facilitate comprehension of information.[15]

The optimal placement of the counterstamps on a Holey Dollar is directly in line with the design on the host coin. In such a situation, NEW SOUTH WALES on the obverse counterstamp runs around the upper half of the inner rim of the coin, while the 1813 date sits in the middle of the bottom half of the inner rim. On the reverse counterstamp, FIVE SHILLINGS runs around the upper half of the inner rim of the coin, while the stems of the twigs sit in the middle of the bottom half of the inner rim.

The obvious question then is, if perfectly aligned counterstamps are the ideal way for these coins to have been struck, why weren’t all Holey Dollars struck in that manner? Could it be that the conditions and circumstances that Henshall was working in have affected his attention to such fine detail?

Henshall’s Working Conditions

It is known that the HMS Samarang arrived at Port Jackson on November 25th 1812,[16] and that the 40,000 silver dollars it carried from Bengal were delivered to Government House for counting and storage on December 5th, 1812.[17]

Acting on advice from Henshall, on June 28th 1813, Governor Macquarie wrote that he expected production of the Holey Dollars would be complete by October 1813: “…the man engaged promises to have the whole cut, stamped and milled in less than three months.[18]” Macquarie issued the first public notice of the coins via Proclamation several weeks later July 10th 1813.[19] In that proclamation, Macquarie stated that “…the silver money shall be a legal tender…after the said Thirtieth Day of September…”[20]

Despite that apparent deadline, the Deputy Commissariat advised that the first Holey Dollars and Dumps were received by the Commissariat on January 25th 1814, and that the remaining coins were delivered in 10 different batches, the last being received on August 2nd 1814.[21] The difference in these dates shows that Henshall’s production of the Holey Dollars was at least four months behind schedule.

Governor Macquarie is widely described as being an energetic and determined man, he would surely have regularly reminded the convict Henshall of the colony’s chronic shortage of specie, and the need to meet the deadline published. Macquarie stated that “…the machine for stamping, milling and cutting out the centre… failed more than once…”, and that there were “…many failures and trials…”[22]

Four different dies were used in the production of the Holey Dollar, clear confirmation that production of the Holey Dollar and the Dump was not a process without challenges. Perhaps uncharitably, Coleman Hyman presumed that “...the die sinker was insufficiently skilled to properly temper the metal from which the dies were made, and they consequently became useless.[23]”

Further evidence of production difficulties is seen in the final mintage of 39,908¼ Holey Dollars. This is widely taken as an indication that “…some of the dollars were destroyed during the operation.[24]” Hyman’s further observation that “Many of the holey dollars are buckled or dished from the effects of the means adopted to perforate and stamp them[25]” emphasizes the challenges Henshall faced in striking the Holey Dollars accurately. Given the challenges encountered with the dies and the machinery, and as production was some 4–5 months behind schedule, it is highly likely Henshall chose expediency over aesthetics when striking the Holey Dollars.

At the time, it was perhaps enough to simply strike a Holey Dollar, let alone produce one that was not dished, and had aligned counterstamps.

The Photographic Representation of Holey Dollars Over Time

If we accept the premise that the optimal placement of the counterstamps on a Holey Dollar is directly in line with the design on the host coin, it is interesting to explore how Holey Dollars have been represented photographically over time. Such imagery can give an idea of how different numismatists at different times have determined the relative importance of the New South Wales counterstamps to the host coin.

As the Holey Dollar is exponentially rarer than a Spanish colonial 8 reales that has not been cut or counterstamped, we could presume that the relative importance of the NSW counterstamps would always be emphasized when a Holey Dollar is photographed.

This is not the case however - current convention appears to be that Holey Dollars are nearly always photographed with the designs host coin vertically aligned, and with the counterstamps falling where they may. It is interesting to explore whether this has always been the case, and if not, why this informal convention might have come about.

Statistical analysis of a summary of how Holey Dollars have been photographed in numismatic books, auction catalogues and price guides over time does not yield any real pattern at all. Just as many Holey Dollars have been photographed with the counterstamps aligned vertically as there have been Holey Dollars with the host coin aligned vertically. No pattern is evident to the way Holey Dollars have been photographed, regardless of which type of publication the photograph appeared in, the year in which the photograph was taken, or the country the photograph was taken in.

Only in the 1970’s is there a discernible preference in the way these coins have been photographed - twice as many photographs in that decade showed Holey Dollars with the counterstamps upright, than showed the host coin upright.

A Statistical Review Of The Alignment Of The Counterstamps On The Population Of Known Holey Dollars

A statistical review of the alignment of the counterstamps on the population of known Holey Dollars reveals that 44 have an obverse counterstamp aligned with the host coin, and 48 have a reverse counterstamp aligned with the designs of the host coin. Just 14 known Holey Dollars have both counterstamps aligned with the host coin.

It is interesting to consider whether this frequency merely reflects the normal probability of die alignment in random circumstances, or whether it is more or less than might be expected. Making use of the clock-based schema devised by Mira and Noble to record the position of the counterstamps on a Holey Dollar, we can begin by concluding that there is a probability of around 8% (1/12) that the counterstamps will begin at any particular “clock” point on a coin. The probability that any obverse / reverse pair of counterstamps might appear in any particular “clock” direction is 0.69% (1/(1212)).

A study of past auction sales records shows that various Holey Dollars have been ascribed as being struck with aligned counterstamps when they begin at either the 9 or 10 o’clock position. This then increases the probability that any obverse / reverse pair of counterstamps might appear to be aligned with the host coin designs is 2.78%. (4/(12*12))

All things being equal, if Henshall did indeed strike the Holey Dollars with the counterstamps struck on the host coins randomly, we would expect to see around 2.78% of known examples (6 or 7 coins) to feature upright counterstamps.

N.B. - It should be noted that the alignment of the counterstamps on a number of known Holey Dollars cannot be discerned as they have been worn away. The statistics referred to here are based on the population of Holey Dollars whose counterstamps can be identified, and so may be slightly different to those expected.

A review of the statistics of the counterstamp alignment on all known Holey Dollars shows that 44/275 (16%) feature an obverse counterstamp aligned with the host coin, and that 48/275 (17.45%) feature a reverse counterstamp aligned with the host coin.

Research shows that no less than 14 Holey Dollars feature aligned counterstamps (that is, with both the obverse and reverse counterstamps beginning at either the 9 or 10 o’clock positions), which is 5.09% of known examples. This is a statistically significant difference to the number of coins that we would expect to see with those characteristics, if the coins were indeed struck randomly.

How then can this statistically significant difference be verified as not being random? My thoughts to date have been that provenance and condition are characteristics that can also be analysed to substantiate or disprove this theory.

Provenance as Verification of an Archival or Presentation Strike

If each of these 14 coins each have a “named” provenance that dates back to the 1800’s, that would be confirmation that such coins were specially struck for archival or presentation purposes.

If these each of these 14 coins remain in superior condition, this also could be an indication that the majority of the Holey Dollars with aligned counterstamps were preserved for archival or sentimental reasons, rather than entering circulation.

Condition as Verification of an Archival or Presentation Strike

12 of the 14 coins (85.71%) with upright counterstamps remain in Very Fine condition or better - this adjectival grade is clearly superior quality to the majority of Holey Dollars known, most of which have been designated lesser adjectival grades.

This superior quality could be an indication that the majority of the Holey Dollars with aligned counterstamps were preserved for archival or presentation purposes, rather than simply being entered into circulation.

Despite that rather overwhelming statistic, only 5 of the Holey Dollars with aligned counterstamps (35.74%) have a provenance that stretches back to the 1800’s. In my opinion, this relatively low percentage does not confirm that these coins were specially struck for presentation or archival purposes.

A further 8 of the 14 coins have “named” provenances, however as those provenances do not stretch back towards the 1800’s, they cannot be taken as an indication that the coins were “specially” struck.

With these statistics in mind, I do not presently believe that either of these supporting characteristics (superior condition and provenance) definitively confirm that Holey Dollars with aligned counterstamps were specially struck for archival or presentation purposes.

These facts do not at all mean that I believe aligned counterstamps are a technical characteristic are of no importance at all - on the contrary, I believe they are very important - more important than the country or date of the host coin, more important than which monarch or portrait type is shown.

While it may not be possible to definitively conclude that these coins were specially struck, as 13 of the 14 coins (92.85%) with aligned counterstamps have been located in “named” collections, this is a very clear indication that such coins appealed to knowledgeable and discerning collectors. The facts may not prove that these coins were specially struck, however they do certainly prove that each of those coins was specially selected by knowledgable and important numismatists.

Alignment and symmetry after all remain aesthetically pleasing, a characteristic that appeals to all discerning numismatists. The alignment and symmetry that each of these coins exhibits is a rare reminder of the challenges Macquarie and Henshall faced when bringing order to Australia’s emerging colonial economy.

-

http://www.smh.com.au/money/holey-sound-decisions–20130924–2ub1g.html ↩

-

Noble; Jim, “Australian & World Coins For Sale By Auction”, Noble Numismatics, Sydney, March 16–17 1988, p 87. ↩

-

Noble; Jim, “Australian & World Coins For Sale By Auction”, Noble Numismatics, Sydney, March 16–17 1988, p 94. ↩

-

Mira / Noble; , “The Holey Dollars of New South Wales”, Australian Numismatic Society, Sydney, 1988, p 24. ↩

-

Gesner; Peter, “Governor Macquarie Lights Up South Head” in Signals - The Australian National Maritime Museum’s quarterly journal, 91, June 2010, p 38. ↩

-

http://www.library.mq.edu.au/digital/lema/1816/1816july.html

-

Glasgott; Joseph, “Govt in the money with Macquarie’s dollar” in the Sydney Morning Herald, August 13th 1982, p 2. ↩

-

Glasgott; Joseph, “Govt in the money with Macquarie’s dollar” in the Sydney Morning Herald, August 13th 1982, p 2. ↩

-

Glasgott; Joseph, “Govt in the money with Macquarie’s dollar” in the Sydney Morning Herald, August 13th 1982, p 2. ↩

-

Mira; William, “A unique holey dollar and dump”, Transport Australia, No 24, 1980, p 3. ↩

-

Gesner; Peter, “Governor Macquarie Lights Up South Head” in Signals - The Australian National Maritime Museum’s quarterly journal, 91, June 2010, p 35. ↩

-

Lane; Peter, “Francis (Frank) W. Giles, a forgotten Adelaide numismatist: his era and legacy” in the Journal of the NAA, 20, 2009, p 97. ↩

-

http://www.britnumsoc.org/publications/Digital%20BNJ/pdfs/1916_BNJ_12_16.pdf ↩

-

Ramachandran, V.S.; Hirstein, William (1999). “The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience” (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies 6 (6–7): 15–51. ↩

-

Enquist, M., Arak, A. & others (1994). Symmetry, beauty and evolution. Nature, 372, 169–172. ↩

-

812 ‘Sydney.’, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), 28 November, p. 2 ↩

-

Andrews; Arthur, “Australasian Tokens & Coins”, Government Printer, Sydney, 1921, p115 ↩

-

Andrews; Arthur, “Australasian Tokens & Coins”, Government Printer, Sydney, 1921, p115 ↩

-

1813 ‘Proclamation, By His Excellency LACHLAN MACQUARIE, Esquire, Captain General, Governor and Commander in Chief, in and over His Majesty’s Territory of New South Wales and its Dependencies, &c. &c. &c.’, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), 10 July, p. 1, ↩

-

1813 ‘Proclamation, By His Excellency LACHLAN MACQUARIE, Esquire, Captain General, Governor and Commander in Chief, in and over His Majesty’s Territory of New South Wales and its Dependencies, &c. &c. &c.’, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842), 10 July, p. 1, ↩

-

Mira, W.J. Coinage and Currency in New South Wales (1788 – 1829) – Metropolitan Coin Club, Sydney, 1981, p26. ↩

-

Historical Records of New South Wales, Volume 7, page 722. ↩

-

Hyman; Coleman, “An Account of the Coins, Coinages and Currency of Australasia”, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893. ↩

-

Myatt & Hanley; Bill & Tom, “Australian Coins, Notes and Medals”, Horwitz Graeme, Sydney, 1980, ↩

-

Hyman; Coleman, “An Account of the Coins, Coinages and Currency of Australasia”, Government Printer, Sydney, 1893. ↩