The 1893 Sydney Proof Sovereign - A Tangible Link to Australia's Most Enigmatic Gold Coins

The 1893 Sydney Proof sovereign is a rare and historic coin - it exhibits technical characteristics that set it apart from gold coins struck for circulation by the Sydney Mint during this era, and may well be linked to the production of two of Australia’s most elusive gold coins - the 1893 Proof Gold Five and Two Pounds.

Only one example of the 1893 Sydney Proof sovereign has been seen on the open market since 1953. This coin was secured by one of Australia’s foremost numismatists during an exclusive ceremony on the day it was struck.

1893 Sydney Proof Sovereign

Brock’s Veiled Head Portrait is Revealed in Sydney

Introduced in 1887, the Jubilee Head portrait of Queen Victoria was described in an official history of British numismatics by Sir Charles Oman as “the greatest disappointment of the century.”[1] News that this unpopular design would be replaced by one engraved by the renown sculptor Thomas Brock was met with rising interest across the British Commonwealth.

The invitation list for the exclusive ceremony marking the start of production of the Veiled Head gold coinage truly was a who’s who of the New South Wales establishment - around 50 of the government’s most senior officials and associated dignitaries came together to be the first to witness the manufacture Sydney’s first gold coins graced by Brock’s portrait.[2]

Lady Duff Cutting Out Discs from Fillets of Gold

Image Source: Sydney Mail 8/7/1893 via Trove

Special Production Ceremony - July 1st 1893

John MacDonald Cameron began his tenure as the Deputy Master of the Sydney Mint in May 1893, just months after the untimely death of his predecessor, Robert Hunt. MacDonald Cameron seems to have wanted to make an immediate impact in his new role, as the exclusive ceremony that launched production of the new designs took place less than 5 weeks after his arrival.

To the degree that Thomas Brock put right the perceived wrongs of Boehm’s depiction of Queen Victoria, the new portrait of Her Majesty was welcomed by those in Sydney’s influential circles - upstanding citizens with firm opinions on the importance of image and reputation.

The unveiling of the new portrait of Queen Victoria enjoyed widespread media coverage after the event, not just within Sydney, but right across Australia. The Sydney Mint buildings were festooned with banners; official photographs were taken and exclusive mementoes were gifted. All of the pomp and ceremony of the occasion highlighted the importance of the change, the number and calibre of those in attendance affirmed the design aesthetic of the new portrait.

Robbery at the AGNSW

Image Source: Evening News 26/12/1893 via Trove

Newspapers of the day tell us this coin was struck in a special ceremony on Saturday July 1st 1893 by Lady Louisa Duff, wife of the NSW Governor. The very first two coins struck were gifted to the Vice-Regal couple by the Deputy Master of the Sydney Mint, who in turn immediately donated them to the National Art Gallery (now known as the Art Gallery of NSW). Unfortunately for the people of NSW, those two coins were stolen in a robbery in December 1893 - contemporary media reports explain they were never recovered.[3]

Queen Victoria - A Benevolent Matriarchal Figure

Queen Victoria has been described as being ”physically unprepossessing” - stout, dowdy and only about five feet tall, yet she succeeded in projecting a grand image.[4] She was well liked during the 1880s and 1890s, when she embodied the empire as a benevolent matriarchal figure.[5]

Victoria was a symbol of the empire who embodied the virtues that the loyal citizens of the Commonwealth strove to live up to. To that end, her image was spread right across the British empire. Coins were one of the most readily-accessible ways by which her citizens were able to see and remember her.

When it was released in 1887, Boehm’s Jubilee portrait ignited a widespread reaction - the average citizen didn’t want to see Queen Victoria in this way, nor themselves by extension.

The new Veiled Head design was eagerly-anticipated, many citizens were keen to see just how the Empire’s most important values were expressed. Brock’s portrait was well received - one article stated that “…the effigy of the Queen remains simple, dignified and comely.”[6]

Contemporary media reports across Australia and in London demonstrate that once the citizens of the Commonwealth saw their monarch portrayed in what they believed to be a graceful and regal manner, it had a calming effect - the change was celebrated and life moved on.

It is interesting to observe that the coins had to first be seen as a work of art before they could be accepted as a desirable medium of exchange.

The Links With Australia’s Most Enigmatic Coins - the 1893 Sydney £5 and £2

1893 Sydney 5 Pound - Counterfeit lead Trial by David Gee

Image Source: Sterling & Currency

There is another aspect of the appeal that this coin has - it is a tangible link to two of Australia’s most enigmatic gold coins - the 1893 Sydney gold £5 and £2. Neither of these coins have ever been sighted, yet there are several reasons to think some may actually exist.

The first is a syndicated article that appeared in a number of Australian newspapers in the days immediately after the exclusive ceremony at the Sydney Mint. The article stated that “On Saturday Lady Duff, at Sydney branch of the Royal Mint, struck off the first pieces of the new coinage. This consists of £5, £2, £1 pieces, and half sovereigns.”[7]

While this might not be the first time mainstream media distorted facts, it’s difficult to understand just how the journalist could have misconstrued the facts in quite the way they did. A complete set of the “new coinage” released in London in 1893 contained 10 coins, not just the 4 gold coins mentioned. This means either the two larger gold coins were struck, or the author of this article took some poetic license with their description of the coins struck.

Another indication that the Sydney Mint may have struck a £2 and a £5 in 1893 lies in an intriguing comment found in the “Catalogue of the Coins, Tokens, Medals, Dies and Seals in the Museum of the Royal Mint”, prepared by William Hocking for the Royal Mint in 1906. William John Hocking began his career at the Royal Mint in 1883 as a clerk, and retired as the Superintendent of the Mint[8] in 1926. During his time, Hocking had intimate access to all areas of the Royal Mint, so we can accept that he prepared his catalogue using at the very least high-quality secondary sources of information, if not an unimpeachable primary information source - the Royal Mint’s archives.

A note on page 325 of the 1906 Royal Mint Museum catalogue by Hocking states that “Specimen five pound and two pound pieces were struck at the Sydney branch mint in 1893.”[9]

Unfortunately Hocking does not provide a mintage figure, nor is any explanation given on the circumstances under which the coins were struck, nor were the dates on the reverse dies mentioned. This could mean that while the Sydney Mint may have struck £2 and £5 in 1893, they may have been dated 1887 - coins with that date are well-known by Australian numismatists.

The final piece of evidence that indicates the Sydney Mint may have struck £2 and £5 coins in 1893 can be found in correspondence between the Sydney Mint and the Royal Mint in the 1920’s. John Honeyford Campbell was Deputy Master of the Sydney Mint between August 1921 and February 1926. In a letter to Hocking dated March 25th 1922, Campbell stated: “The [1887 Sydney £5 and £2] dies are still here, as are the dies for the 1893 Five Pound and Two Pound issue.”[10] This authoritative reference affirms at the very least that the Sydney Mint received dies, which at least keeps the possibility of them being used open.

The 1893 Sydney Five Pound and Two Pound have never been discussed even in passing in any Australian numismatic publication I have seen to date. If they ever were to be discovered, they would without doubt be regarded as stunning heirlooms equal in appeal to any of Australia’s rarest gold coins.

Henry Carey Dangar

Image Source: NSW State Parliament

We could take Campbell’s comment in 1922 to mean that the “specimen five pound and two pound pieces … struck at the Sydney branch mint in 1893” were indeed dated 1893. If that is the case, the 1893 Sydney Proof sovereign is a direct link to two of Australia’s most enigmatic coins.

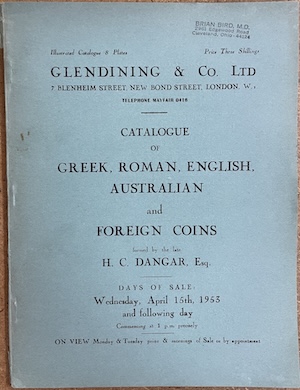

Provenance - Henry Carey Dangar MLC

The 1893 Sydney Proof Veiled Head sovereign hails from the estate of the NSW politician Henry Cary Dangar - he was a well-connected, wealthy and focused numismatist. The auction of Dangar’s collection is acknowledged as one of the most important Australian coin collections sold in the first half of the 20th century.

Horace WIlliam Dangar (Back Row, Centre)

Image Source: Australian War Memorial

Dangar died in 1917, his son Horace William Dangar inherited his father’s collection. Horace William was one of Australia’s most senior military officers, he died in 1923. It is not yet known who inherited H.W. Dangar’s coin collection upon his death.

The sale was held in London by Glendining across April 15th and 16th 1953, it contained a large number of incredibly rare coins from Australia, Britain and the ancient world.

First Sold in London in 1953 - Lot 229

Lot 229 in the Dangar collection was described as:

“Sydney Mint, Old Head Coinage, Sovereigns 1893 (2). Both brilliant.”

This sovereign (ex that pair) subsequently appeared in a Spink Australia auction in Sydney in 1977; then again in 1980 and in 1989; via a KJC auction in Sydney in 2005 and via an IAG auction on the Gold Coast in March 2021.

Across those six different auctions, the coin has variously been described as being “Brilliant”; “select Uncirculated”; “Proof-like gem”; “A brilliant proof-like specimen”; “Proof” and finally “proof-like”.

This is an incredible variation in written attributions, and although highly unusual is not unheard of when it comes to specially-struck coins that don’t neatly conform with the criteria that most numismatists expect from “proof” coins.

Dangar Collection Auction - Glendining, London 1953

Clearly A Coin Apart

With an incredibly sharp strike, a liquid appearance to the fields and a matte texture to the relief, the appearance of this coin shows it to be clearly different to a premium quality circulation strike.

Despite this undeniable superiority, the coin does not exhibit the fully-mirrored surfaces and deeply frosted relief that most collectors expect to see in a proof record coin. This is the cause of widespread mis-attribution seen over the past 4 decades when the coin has been offered for sale via auction.

The question becomes then, if the coin is not a circulation strike and it is not a proof strike, just how should it be attributed to ensure that its special status is acknowledged without misrepresenting the technical characteristics it has?

Finding an objective standard by which this decision can be reached is not simple - although the circumstances of the coin being manufactured were broadcast through several local newspapers in Sydney in 1893, those articles did not explicitly record the way in which the coins were struck.

Determining an appropriate classification of the coin can be made by comparing the technical characteristics it has against an objective standard.

Perhaps the only non-commercial and objective standard published in Australia on this subject is an article in the South Australian Numismatic Journal in July 1955.

South Australian Numismatic Journal - The Earliest Definition of a Proof Coin

Written by Syd Hagley and James Hunt-Deacon, President and Secretary of the South Australian Numismatic Society respectively, it was intended to provide an exacting definition of what a proof coin is, such that collectors could have confidence in adding items to their collections.

Hagley and Hunt-Deacon provided the following list of definitions, and advocated ”the adoption of the above definitions” by collectors and dealers across the nation:

South Australian Numismatic Society Definitions - Proof Coins

Technically the first impressions from the dies; but as a numismatic term it has a wider significance. Five separate classes of proofs are here treated:

1. Coins struck from selected polished dies on highly Polished flans. Except for the high Polish and the clarity of impression they are identical with the current coin, and a little wear removes all traces of their once having been proofs. (The proof Australian coins of January 1937-39 belong to this class. Since these were the only years in which proofs were officially minted in Australia the coins struck as specimens for museum collections in 1953* and preceding years can hardly be given the status of proof coins.)

2. Coins struck from dies, the incuse parts of which have been blasted or acid-etched and the field polished to a mirror finish. They are recognized by their high polished field and matt surface of letters and types.

3. Coins struck from selected dies, but rendered different from the ordinary issues, i.e. plain instead of milled edge.

4. Coins struck from dies which have been entirely sandblasted or acid etched.

5. Coins struck by any of the above methods, but in a different metal from that normally used, eg a penny struck in silver.

Five different classes of coin all covered by one single term is surely an unacceptable level of classification - two coins with different technical characteristics should not be covered by one term, as it inhibits accurate identification and classification.

If we were to re-frame the above title as “Archival and Presentation Coins”, the 5 sub-classifications appear to be broad enough in scope and individually accurate to cover all known archival and presentation strikes.

If the above list were built upon to account for the inadequacies it has, each classification may be described accordingly:

Archival and Presentation Coins

1. Specimen - struck from selected polished dies on highly polished flans;

2. Proof - struck from dies, the incuse parts of which have been blasted or acid-etched and the field polished to a mirror finish;

3. Pattern - rendered different from the ordinary issues, i.e. plain instead of milled edge;

4. Matte Proof - struck from dies which have been entirely sandblasted or acid etched;

5. Off-Metal Pattern - Coins struck in a different metal from that normally used.

Based on the above definitions, the 1893 Sydney sovereign is clearly a proof strike, produced on the first day of minting and personally presented to a well-connected, wealthy and focused numismatist.

Addendum:

We are pleased to report that following a physical inspection of this coin, staff at the Royal Mint Museum in Wales have authenticated the coin as a proof:

“The quality of strike is consistent with a proof sovereign struck at the Sydney branch mint, the field clearly being polished on both sides and the surface quality is very good. Under magnification it is possible to see that the Sydney mint mark has been quite crudely engraved. This is not, however, a reason to question the piece’s authenticity, particularly as the specifications and composition are consistent with a piece struck in Sydney. The quality of engraving can most likely be explained by the skills of the engraving department at Sydney who were responsible for creating the mint mark on the dies used to strike the coin.

A detailed comparison of the coin against records of other such pieces previously authenticated shows that this is the same coin that was examined and authenticated as genuine by the Royal Mint in November 1980.”[11]

This independent authentication report, prepared by the ultimate authority on sovereigns of the British Commonwealth, when coupled with previous auction lot descriptions, confirms that this is the only example of this coin to be available to collectors since 1953.

The full provenance of the coin is as follows:

Ex Sydney Mint on date of manufacture - July 1st, 1893;

Ex H.C. Dangar collection; H.W. Dangar collection and Glendining auction - April 15th & 16th, 1953 (Lot 229);

Ex Spink Australia Sale 1 (October 1977), Lot 500;

Ex Spink Australia Sale 4 (November 1980), Lot 577;

Ex Noble Numismatics Sale 30 (November 1989), Lot 1321;

Ex KJC Coins Auction 1 (June 2005), Lot 810;

Ex IAG Auction 93 (March 2021), Lot 646.

[1] GP Dyer and Mark Stocker; "Edgar Boehm And The Jubilee Coinage" in the British Numismatic Society Journal, 54, 1984, p 274.

[2] "THE NEW COINAGE." The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954) 3 July 1893: p3.

[3] "Daring Burglary." Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1919) 30 December 1893: P10.

[4] Hibbert, Christopher (2000), Queen Victoria: A Personal History, London: HarperCollins, pp. 61–62

[5] Marshall, Dorothy (1972), The Life and Times of Queen Victoria (1992 reprint ed.), London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p210.

[6] THE NEW COINAGE. (1893, July 3). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3.

[7] "The New Coinage." National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW : 1889 - 1954) 3 July 1893: p2.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_John_Hocking

[9] Hocking; WJ, “Catalogue of the coins, tokens, medals, dies and seals in the museum of the Royal Mint", Royal Mint, London, 1906, p 325.

[10] Campbell to Hocking; 25/3/1922; Royal Mint Correspondence; NSW State Archives

[11] Private correspondence, Royal Mint Museum, August 22nd 2023

Comments (6)

PCGS Regrading

By: Ken Mansell on 12 January 2024After receiving confirmation from the Royal Mint as to it's status, have PCGS now regraded this coin accordingly as "Proof"?

Only one?

By: SovCollector on 8 January 2024Fascinating research, well done. Some slightly contradictory information here, though: https://coinworks.com.au/Unique-pair-of-Proof-1893-Sovereign-and-Proof-1893-Half-Sovereign-struck-as-Coins-of-Record-at-the-Sydney-Mint~70668

Sterling and Currency Response

I have only just seen this comment now, I need to set up some kind of notification system when we get feedback like this so I don't miss them. Fair Point! I'd suggest though that as those coins both have a plain edge, they are more patterns rather than proofs, and so are quite different to the proof discussed here. I haven't seen any information that might indicate when in 1893 those patterns were struck, I haven't seen them appear via auction previously either.

Perseverance in Numismatic Research Pays Off

By: Vincent Verheyen on 7 January 2024This article is a great example of how diligent research work can add to our knowledge of Australian numismatics. Andrew has the library, contacts and patience to confirm his theory that this sovereign was a proof strike. Simply expecting 3rd party graders to have the background experience to evaluate ultra-rare Australian coins correctly is ill-advised. Provenance is becoming ever more important when dealing with valuable coins, knowing your coin has been in the hands/collection of an eminent collector provides greater surety and ownership satisfaction.

re 1893 article

By: Bob Gibson on 7 January 2024What an interesting read. You are to be commended for your tenacity and commitment in having this coin properly described. Confirms my opinion that PCGS is not the be all and end all when it comes to grading.

PCGS Regrading

By: Ken Mansell on 6 January 2024After receiving confirmation from the Royal Mint as to it's status, have PCGS now regraded this coin accordingly as "Proof"?