Shinplasters and A Lack of Real Money - A Primer on Privately Issued Currency Notes in Australia

The average person might often feel like there is never enough money in the world (for them at least), but the reality is that in modern times, money issued by the government is abundant and is nearly always available when it is needed to act as a medium of exchange.

This hasn't always been the case - there have been many times in different parts of the world, certainly in regions of Australia as recently as the 1930s, when day to day business was restricted simply because there wasn't enough money available. Numerous Australian country towns established during the 1800s were hundreds of miles away from their closest bank, which meant that any coins or banknotes picked up in trade by visiting merchants or travellers were removed from the local economy, and couldn't be easily replaced.

There Are No Banks in the Middle of Nowhere

William Steven Weigh owned a general store in Boulia (North-Western Queensland) in the early 1900s. In response to an article published in Sydney's Sun newspaper in January 1922, Weigh stated: "The nearest bank to Boulia is at Cloncurry, nearly 200 miles away, and although we do occasionally see Treasury Notes, they are no by any means as plentiful as shinplasters. It is absolutely necessary for our business to issue our own notes and I.O.U.’s; we could not carry on without them."

Another general store owner that corresponded in the same newspaper was George Watson, who operated the Rankine Store in the Northern Territory. Watson confirmed the circumstances that led to many shinplasters being issued: "You will understand that small change is very scarce out this way, & gold we never see now ... Our nearest Bank is in Cloncurry 340 miles from here."

History shows that many businesses and even private individuals didn't wait for the situation to be magically resolved, they stepped into the breach and facilitated local trade by issuing their own currency notes.

To the degree those businesses and individuals enjoyed the confidence of their fellow citizens, those notes were used in trade regularly and widely, even by people completely unrelated to the business that issued them.

The way an individual or business issues their own currency and the fundamentals required for it to be successful is far easier to understand than the way money is created in the modern monetary system, for that reason alone, shinplasters are a valuable topic of study and examination.

Privately-Issued Currency - Organic and Unstructured

The field of privately-issued currency is, by its very nature, organic and unstructured - many different forms were issued and many different, often colourful and archaic, terms are used to describe them.

This article seeks to bring some order to the Australian experience of privately-issued currency and shares stories of several different issuers to illustrate the process by which money is created, and the factors required for it to be successful.

Shinplasters - Used by Soldiers in the American Revolutionary War

The term "shinplaster" has been used to describe paper currency notes in several different locations and at several different points in history. It was first adopted in the context of currency in the United States, during the American Revolutionary War (1775 ~ 1783).

A Continental Currency Note

A "shinplaster" was, at first, a piece of paper soldiers put in front of their boots to cushion their shins against chafing and rash. Soldiers walked long distances to and from battle, so comfort and injury prevention were paramount. [1]

During the American Revolutionary War (between 1775 and 1783), each of the 13 newly-formed US states issued their own paper currency notes to facilitate trade at a time when coins were in limited supply. The Continental Congress also issued a wide range of paper currency notes, many in odd and small denominations.

The colonial and continental currency notes all quickly became worthless, leading to the origin of the expression "not worth a continental." [2] The valueless paper currency notes were then said to have been used by soldiers to pad their boots.

Shinplaster Notes Were Also Used in Colonial Canada

Throughout much of Canada's colonial period, merchants and even individuals issued their own paper currency notes. These fractional notes (known as "bons" after “Bon pour”, the French equivalent of “good for”, the first words on many such notes) circulated widely throughout Canada during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and were also referred to as shinplasters. [5]

A Canadian shinplaster note

The term "shinplaster" came into popular use a second time in Canada, just after the US Civil War. One of the ways the Canadian government addressed the problem of an acute shortage of silver coins in circulation at that time was to introduce a 25¢ banknote in 1870, payable in gold upon demand.

These notes were similar in value and physical size to many of the bons, colonial and continental notes issued across Canada and the United States, so were also referred to as shinplasters. Unlike the US notes, the 25¢ "shinplasters" issued by the Canadian government held their value and retained the confidence of the public over the long term - they remained in circulation for 65 years. [4]

Shinplasters, Calabashes and Other Forms of Private Currency Notes Circulated In Australia

Privately-issued currency notes of one form or another were an important component of the Australian monetary system from the early 1800s right through to the 1930s. The varied privately-issued currency notes used throughout Australia can be classified as one of several different types, the classification depends on the following criteria:

- Issuer or drawer (who is making the promise);

- Drawee (the entity that will make the payment, if not the issuer or drawer);

- Promise (exactly what the issuer's commitment is);

- Payment method (whether in coin, specie or in goods to the value of); and

- Amount (whether it is fixed or variable);

- Payee or beneficiary (whether specifically identified or not);

- Date of payment (whether on-demand or after a future date).

Once the above characteristics have been identified, an Australian privately-issued currency note can be classified into one of the following categories:

- Currency notes;

- Promissory notes;

- Shinplasters;

- Calabashes;

- Sight notes;

- Bill of Exchange.

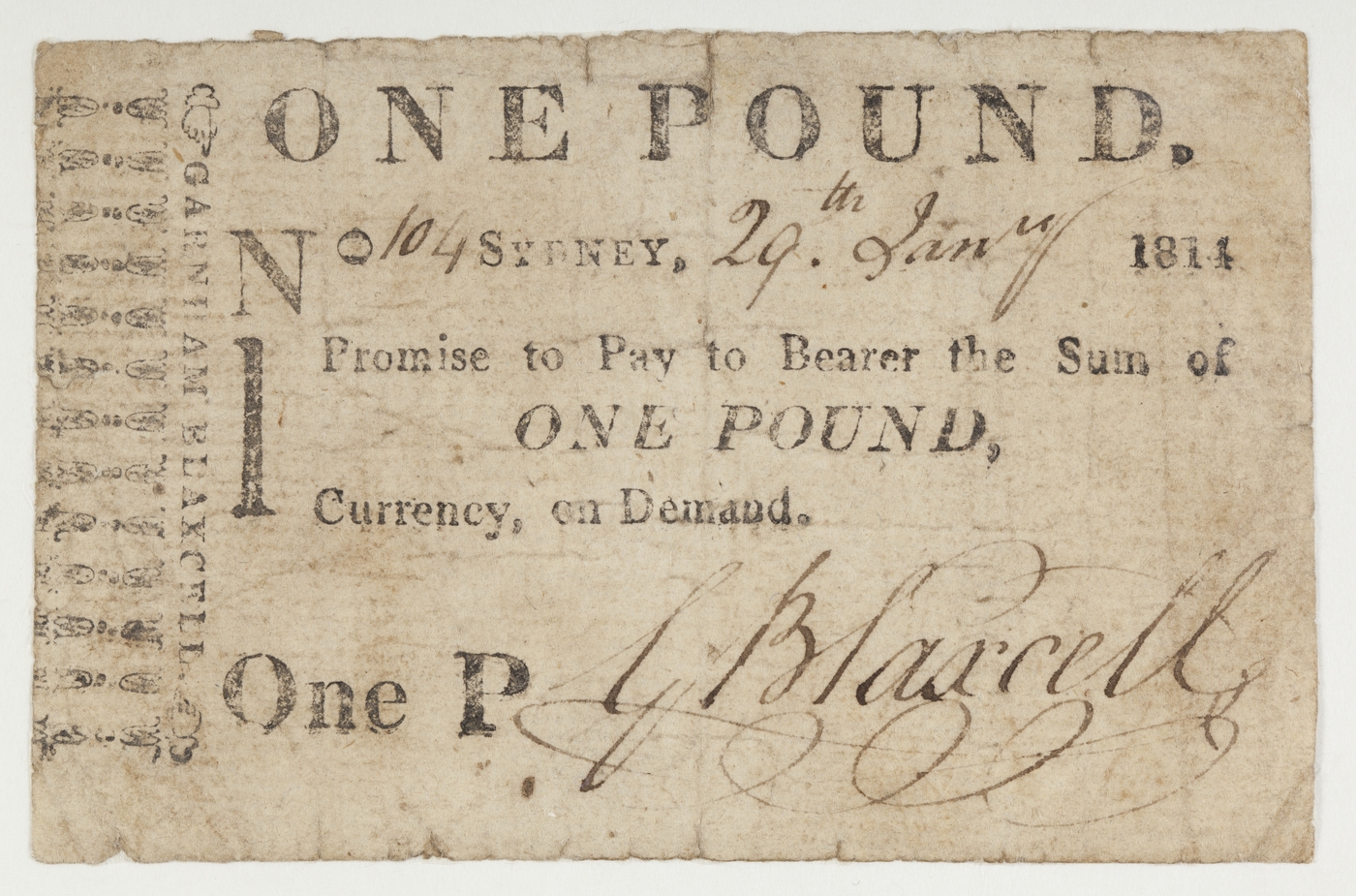

Blaxcell Currency Note

What Is A Currency Note?

A currency note is described as being “A private bill issued by a person or a firm (not a bank), payable on demand, not necessarily in specie, and with an explicitly stated (printed or engraved) regular denomination." Currency notes are generally issued by private individuals (not businesses) and were dated and signed by the issuer. These notes circulated alongside British coins (Sterling) with varying degrees of success and acceptance. So prevalent were these currency notes in colonial New South Wales that "currency lads and lasses" was the term used to describe the first generations of native-born white Australians. Sterling was intended to indicate coins and thus (British) people who could be accepted without question, while currency was intended to indicate paper notes and people that should be regarded as poor substitutes for solid value, and thus not to be trusted.

Featured Note: In his prime, Graham Blaxcell was one of colonial Sydney's richest merchants. By the time this currency note was issued, Blaxcell had suffered an extended run of financial difficulties. With a debt measured into the thousands of pounds, Blaxcell left the colony in 1817 and died at Batavia shortly after that. One wonders how many were left holding his notes at that time.

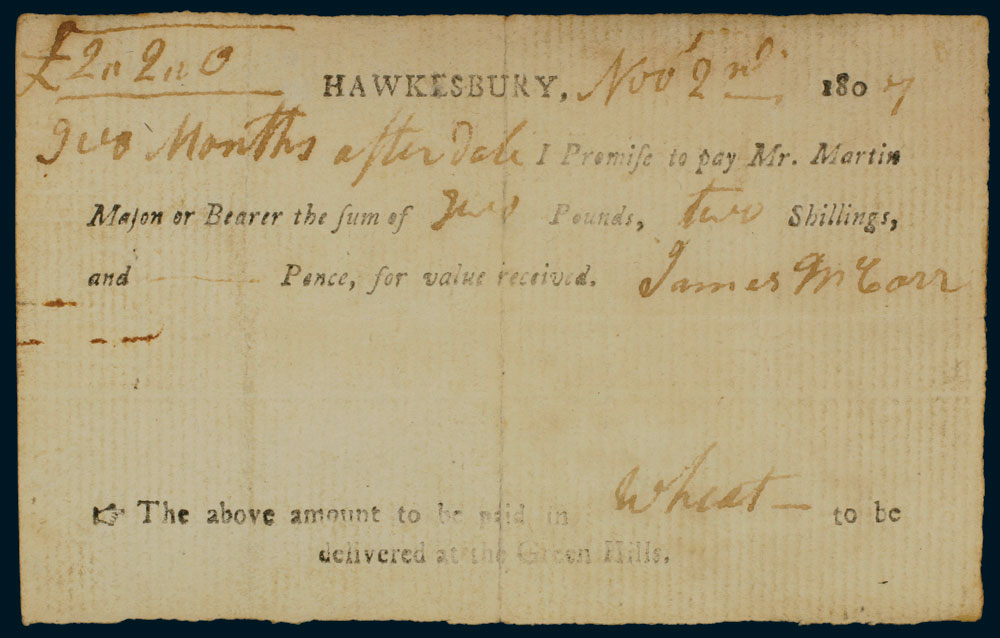

James McCarr Promissory Note

What Is A Promissory Note?

A promissory note is described as being “A private bill in some such form as “I promise to pay”, not necessarily payable on demand, drawn on the issuer or his agent or bank. Applied here only to those without a definite printed denomination, in which case it is called a currency note.” Promissory notes are also mainly issued by private individuals, the value is generally written in by hand. Some Australian promissory notes are entirely hand-written. Promissory notes had the same legal standing and level of acceptance currency notes.

Featured Note: James McCarr was a landowner in what is now known as "the North Shore" of greater Sydney. Little is known of him or his ability to honour the debts that he went into by issuing promissory notes such as this one.

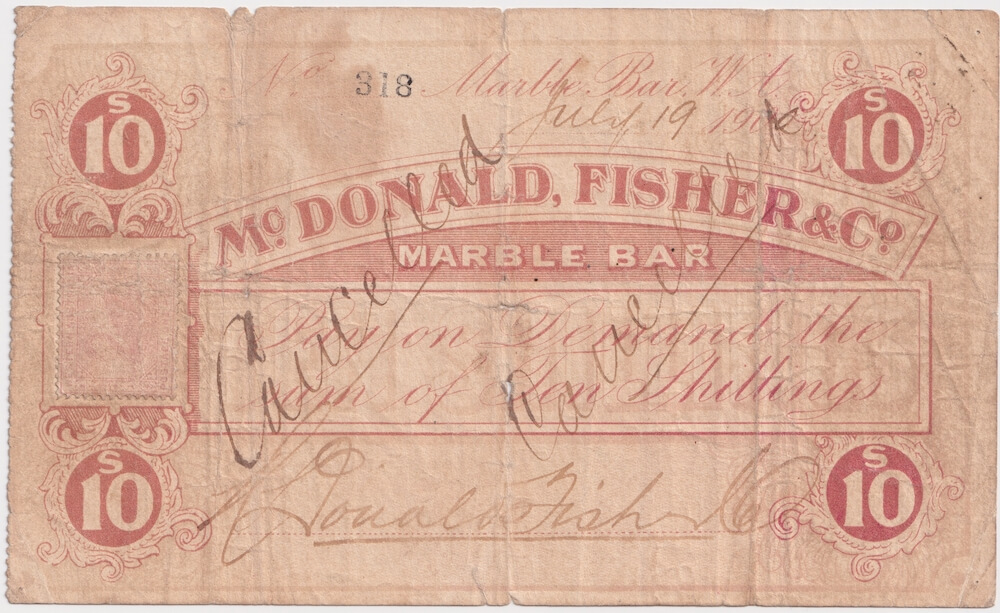

McDonald Fisher & Co Shinplaster

What Is A Shinplaster?

A shinplaster is described as being "A promissory note from an individual or company, promising to pay a stated amount on demand." All of the Australian private currency notes known to collectors as "shinplasters" have been issued by businesses. Shinplasters tend to be issued on specially-prepared printed forms, each with an individual serial number.

Featured Note: McDonald Fisher & Co ran a general store in Marble Bar (North-West Western Australia) between 1896 and 1902. Their notes were highly regarded, as can be seen in this passage from "To The Bar Bonded", a local history of Marble Bar: "McDonald, Fisher and Co. introduced the "shinplaster" to Marble Bar. The "shinplaster" was paper money issued by many traders in outback Australia in lieu of ready cash, a form of currency honoured by all. This partnership ceased in 1902 when Fisher left for England, having resided in the Bar for seven years."

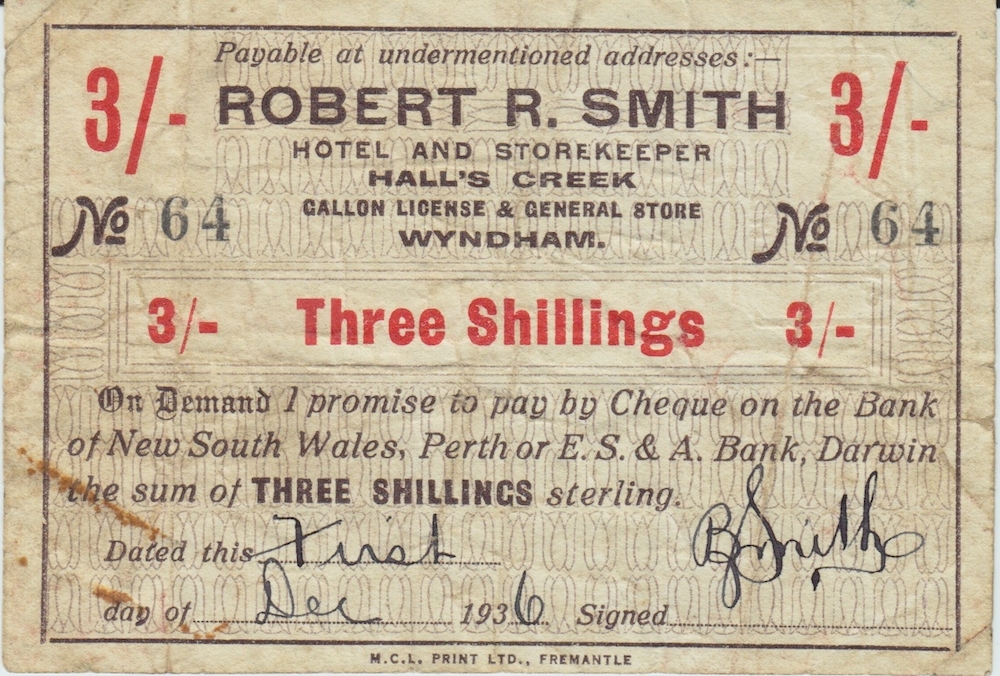

Robert Smith Calabash

What Is A Calabash?

One proposed definition of a calabash is that it is similar to a Shinplaster, in that it is "A promissory note from an individual or company, promising that their bank will pay a stated amount on demand." According to this taxonomy, the key distinction between a shinplaster and a calabash is that the payee is the issuer's bank, and is not the payee themselves. There are indications that this definition may be somewhat over-structured.

The term "calabash" may instead be a different colloquial name used to describe shinplasters, one that is specific to South-West Queensland. I am yet to see any published evidence that this term has been used to refer to currency outside Queensland.

One indication that calabash is simply another name for shinplasters can be found in an article in the Townsville Bulletin newspaper dating to September 2015, where the author concluded: "Shinplasters were also called calabashes in some parts of Queensland."

In his book on the history of Toowoomba [Morass to Municipality], Robert Dansie states "In settlements such as the Darling Downs, Drayton, and Ipswich, coins and notes were very scarce, and for many years after settlement, banks did not set up branches or agencies in the remote communities. In those places, squatters and traders evolved a system of issuing I.O.IJ.s, orders and promissory notes for denominations less than £1 — in fact for as little as one penny or one halfpenny. Such pieces of paper became pseudo-legal tender, accepted as payment for goods and services, and passing from one person to another in much the same way as coins, notes, and some cheques do today. The documents were referred to in other places as 'shinplasters' but in and around south Queensland they were universally known as 'calabashes'. The original signatory on a calabash was expected to redeem it for its stated value, and to guarantee its worth." [7]

Francis Cumbrae-Stewart was the foundation registrar and librarian of the University of Queensland from 1910. In a paper written by him covering the subject of calabashes, he stated that "Calabash is an I.O.U. for a sum less than £1." [8]

An anonymous article in Sydney's Sun newspaper in January 1922 recounted the varied system of money that was in use in outback Australia up to that date: "There was a paper currency In vogue, with every storekeeper, or publican, or butcher, as the case might be, his own mint. All had their own paper money, variously designated 'shinplasters' or 'calabashes'." Later in the same article, the Wanderer stated: "I have never seen a 'shinplaster' or 'calabash' or 'blanket' as the IOU's out west are termed, for any amount less than 3 shillings..." Further again, he states: "It is the 5/- IOU note which is variously termed 'shinplaster', 'calabash' and 'blanket'." [9]

Outside numismatics, the term calabash is primarily used to describe a tree and a vine that yields a gourd or fruit that is dried and made into kitchen utensils when dried. [8] The link between the tree and vine and privately-issued currency notes in Australia is not yet known. My own speculation lies in the similarity between the Queensland Bottle Tree and the French-named Calabash tree - early settlers in Moreton Bay refer to calabash gourds regularly well before any private currency is discussed. Just how the trees relate to the notes I have no idea.

Featured Note: As the image of the front of the note above indicates, Robert R. Smith was a storekeeper and hotelier in Hall's Creek and Wyndham in North-West Western Australia. We have not yet encountered any information online covering the biography of Mr Smith, nor the degree to which his notes circulated.

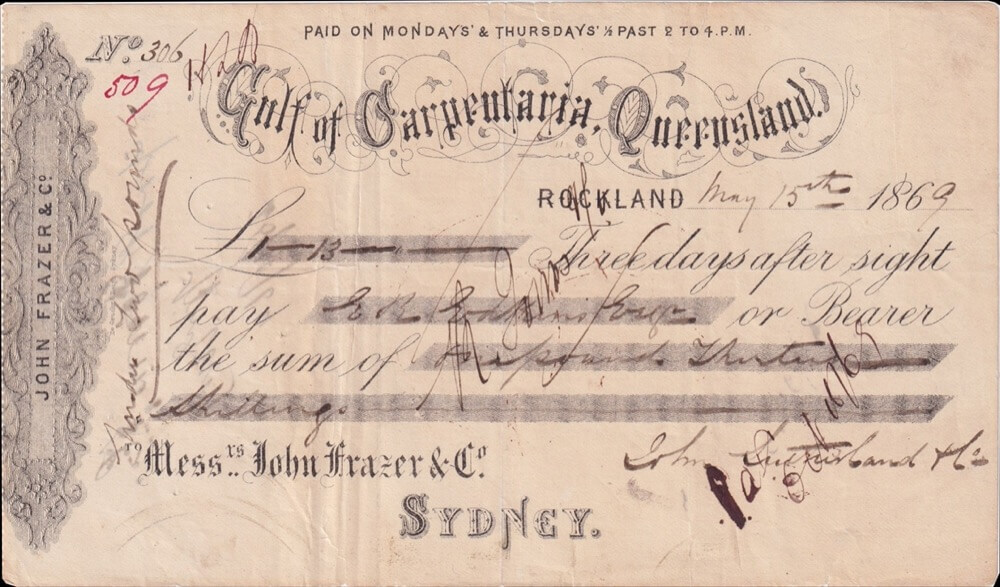

John Frazer Sight Note

What Is A Sight Note?

A sight note is "a promise to have their bank pay a certain sum of money, after a specified future date." The drawee of a sight note was generally a bank in a location geographically distant from the issuer or drawer, the sum payable was only due at a future point in time. The term "sight note" refers to the clause within the promise made, whereby the sum payable was only due a certain amount of days after "sight", i.e. a certain number of days after it had been presented to the drawee. This clause was intended to assist in the prevention of theft, as the days after "sight" or presentation allowed the drawee to contact the issuer to verify that the sum due was indeed due to the bearer.

Some sight notes have been "endorsed" by the initial payee in transfer to another individual. Sight notes are generally issued by businesses, and not private individuals. Sight notes seem to have been reserved for transactions much larger than those that would be catered for by a shinplaster or calabash.

Featured Note: This particular note was issued by John Frazer, a Sydney businessman with diverse commercial interests. A text named "Australian Men of Mark", published in Sydney in 1889 provided the following background information on John Frazer:

"The late Honourable John Frazer, MLC, began life in the colony of New South Wales nearly fifty years ago as a penniless boy. Hard work, relieved by heroic attempts at self-culture, marked his early days. Then an attempt at a business on his own account was made, and this gradually expanded and grew until to-day we find the firm of Messrs. John Frazer and Company, which he founded and which inherits his honourable name, occupying a position in the very forefront of the great importing houses of this pre-eminently commercial city."

"The Honourable John Frazer was closely identified with many of the leading commercial and financial institutions of Sydney. He was a director, and for a long time chairman, of the Sydney Fire Insurance Company. He had served on the directorate of the Australian Joint Stock Bank, the Mutual Life Assurance Company, the Australian Steam Navigation Company, the Australian Gaslight Company, the Commercial Union Insurance Company, and other public institutions. At the time of his death, he was a director of the Commercial Bank. As a public-spirited citizen, he was known by his benefactions to the Sydney University and to St. Andrew's Presbyterian College within that University. And he has left a familiar memorial of his liberality by his gift to the people of Sydney of the two " Frazer Fountains," which stand at the entrance to the Hyde Park and the Domain."

Before his retirement in 1869, Frazer included several cattle runs in Queensland among his commercial interests. The Australian Dictionary of Biography states: "From the mid-1860s Frazer speculated in land in Queensland and by 1871 had four runs of his own and eighteen in partnership." This note relates to what I understand is a property named "Rockland" near the Gulf of Carpentaria, while other sight notes issued by him cover areas such as Caamboon and Walloon.

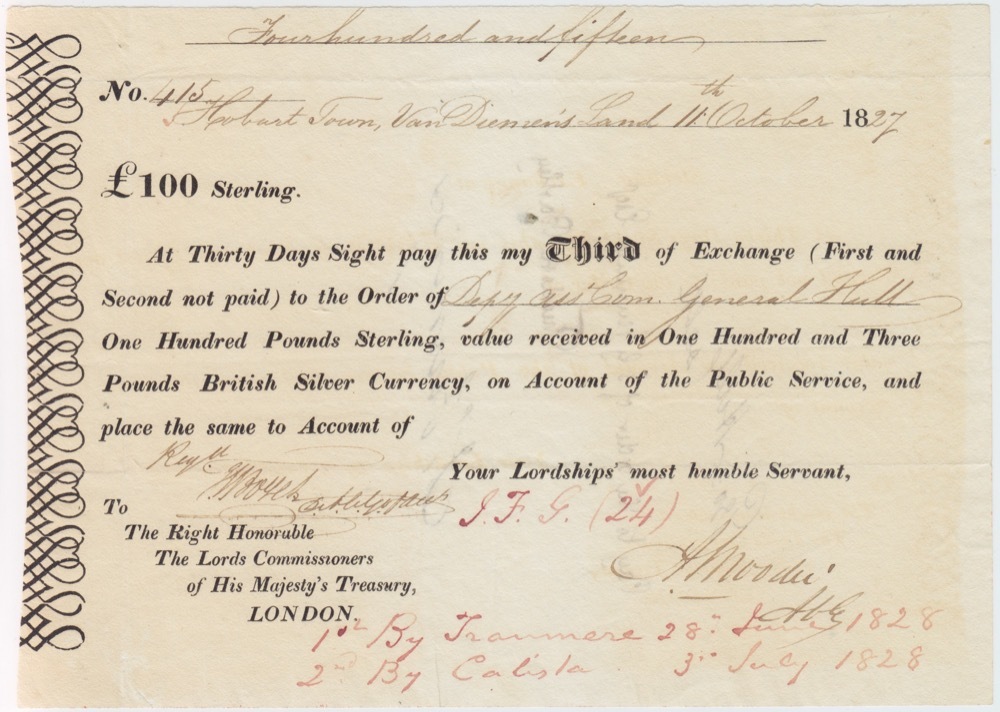

What Is A Bill of Exchange Note?

Van Diemen’s Land Bill of Exchange

A bill of exchange is also similar, in that it is "...an unconditional order in writing, addressed by one person to another, signed by the person giving it, requiring the person to whom it is addressed to pay on demand, or at a fixed or determinable future time, a sum certain in money to or to the order of a specified person, or to bearer." [6]

Bills of exchange were created in triplicate - for the drawer, the drawee and the payee. As such bills were generally used to transact making use of funds held by banks based in London; the first two copies were generally sent via different ships to London, the third was generally held by the issuer or drawer.

Bills of exchange were transferable if they were "endorsed" by the initial or a subsequent payee - they could be used in exchange by individuals or businesses quite independent of the initial payee or drawer.

Featured Note: This particular third of exchange was endorsed by Affleck Moodie, the officer in charge of the commissariat between late 1821 and 1839.

Moodie is described as being "one of the finest Commissariat Officers to come to Hobart Town. He was ‘applauded for his resistance to an offered bribe’ which he reported in 1822. Amidst the irregular tides, which at times threatened to engulf the entire VDL Civil Service, he seems to have stood out as a beacon of honesty. On 16 August 1826, Governor Arthur had written of him to BATHURST, His conduct has been during my command uniformly zealous and correct and of his position Assistant Commissary General, ‘no appointment can involve greater responsibility in a country where every degree of ingenuity is exhausted to devise means of plunder."

The recipient is made out as being James Ogilvie, a wine merchant and publican that arrived in Hobart in February 1822. His eulogy had this to say of Ogilvie: "In short, he was a good member of society, and a worthy example of persevering industry."

The first copy of this bill of exchange was sent via the Elizabeth on March 1st 1828; the second by the Meadow on April 20th 1828.

The Characters and Character Behind Australia's Shinplasters

The brief biographical notes covering McDonald Frazer & Co and John Frazer above give us some idea of the characters and the character of some of the men that issued shinplasters in their local communities. Although the following description is most likely shaped by clear survivorship bias, the impression I have of the (successful) businesses that issued their own currency notes is that they were often quite active in the community in a range of other capacities. It may well be that most businesses that issued shinplasters failed due to malfeasance and faded into obscurity, the extant historical record is all we can work with at this time.

Other personalities linked to Australian shinplasters are:

George Espie: a well-known merchant in Charleville (Southwest Queensland). "One-time Mayor Of Charleville George Martin Espie was one of the most colourful personalities to occupy the position of Mayor of Charleville. He came to this town from Bendigo about the year 1888 to join his brother, D. E. (Ted) Espie, and the brothers, with their bullock teams, ranged the south-west from the Warrego to the Cooper. He commenced storekeeping about the year the railway went on to Cunnamulla and continued at that occupation until his death in 1944. A forceful character, he was twice Mayor of Charleville, and many times an Alderman. He was a founding shareholder in Qantas and noted for his progressive ideas, and for the aggressive energy with which he pushed them."

James Burns: It also states that "...by the early 1980s, Burns Philp was a conglomerate that controlled over 200 companies involved in about 100 separate industries."

Reginald Breene: operated a general store and post office exchange in Eromanga (SW Qld)

Reginald was responsible for the construction of the first main road from Quilpie to Eromanga as well as for the construction of the sewerage system in Quilpie. Breene is known to have been: Coroner; Justice of the Peace; Chairman of Quilpie Hospital Board; Deputy Chairman Quilpie Shire Council; Member of Quilpie Fire Brigade Board; Secretary of Eromanga Race Club.

Bill Weigh: ran a general store in Boulia (QLD) in the early 1900's, He is variously listed as being: the Boulia Shire Clerk; a member of the Great Northern Rabbit Board and Honorary Treasurer of the Boulia Hospital.

George Shenton:

Glossary: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-326186376/findingaid

[1] Marching To War: The Production of Leather and Shoes in Revolutionary Pennsylvania; David L.Salay

[2] Newman, Eric P. The Early Paper Money of America. 3rd edition. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 1990; p17.

[4] Powell; James, "A History of the Canadian Dollar", Bank of Canada, Ottawa, 2010, p 31.

[5] Powell; James, "A History of the Canadian Dollar", Bank of Canada, Ottawa, 2010, p 92.

[6] https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2012C00128

[7] Dansie; Robert, "Morass to Municipality", Darling Downs Institute Press, Toowoomba, 1985, p 63.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crescentia_cujete

[8] Catalogue of the Hayes Manuscript Collection; #465; Cumbrae-Stewart, Francis William Sutton; "Calabashes"

[9] The Wanderer; "Queer Money" in the Sun Newspaper, January 15th 1922, p 13.

Comments (1)

Excellent and interesting article to read on earl

By: Debbie on 2 July 2023Thank you, Andrew Very interesting and I agree very important to our numismatic and Australian history records. I feel that Pre Federation notes are certainly an important part of our history and that they should be recognised equally alongside other Australian notes. Look forward to reading more on this topic. Regards Debbie