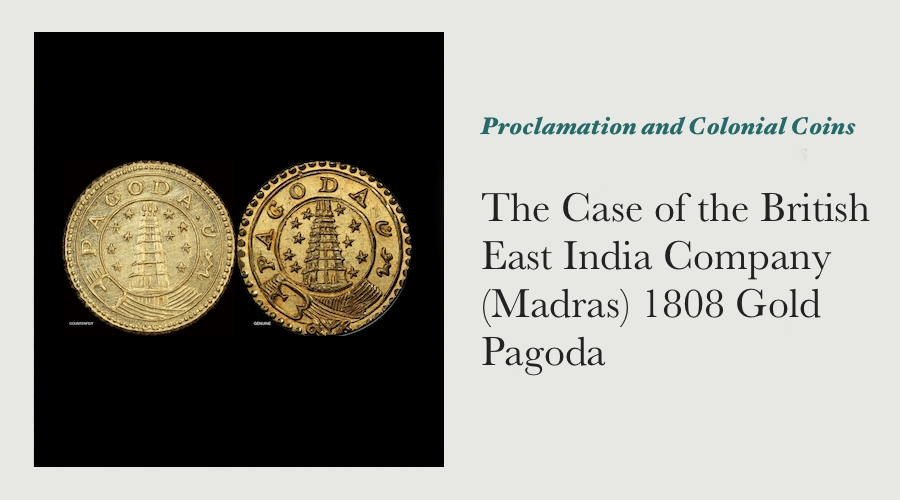

The Case of the British East India Company (Madras) 1808 Gold Pagoda

We bought up a large collection of proclamation and colonial coins some time ago - some were “slabbed” (by both PCGS and NGC), while the remainder were raw.

We described the coins accordingly, took photos of them and posted them to our website - in time, the coins found new homes and all ended well.

Apart from one fly in the ointment.

One of the coins was an 1808 Gold Pagoda, a solid coin struck by the Madras Presidency of the British East India Company. The pagoda is a denomination that had circulated in Southern India for hundreds of years, and was then adopted by the European colonial powers that had settled in or around Madras.

Cracked Out of a Slab Prematurely

The particular gold pagoda that we had acquired was in a slab that indicated the coin was genuine, but had been cleaned. Most collectors that are active in this area aren’t particularly fussed about their coins being independently-graded, so we cracked the coin out of the slab it was housed in, and offered it “raw”. That was when the fun really began!

I was contacted by a few collectors that are active in this area, they each advised that the coin we were advertising was counterfeit. I took their feedback with a grain of salt, whatever uncertainty may have been in my mind to begin with was cleared up fairly quickly once I was able to compare images of our coin with known genuine examples.

Numismatics is an area rich in experiential learning, we learn by taking a risk and accepting the consequences of each transaction as they play out. If a collector or dealer is prudent and doesn’t stray too far into areas they either don’t understand or aren’t experienced in, the chances of coming unstuck are actually quite rare. This coin just happened to be one of those rare times when it’s possible to lose money even when acting prudently.

I know some of you reading this will say if the coin was still in the holder the independent grading company that slabbed it had placed it in, their authenticity guarantee would have still been valid. Once it’s been cracked out though, there’s no real way to substantiate the prior authentication, which would well have been mistake number two.

About 20 years ago, I vaguely recall hearing stories of a “colourful” British rare coin dealer who was marketing these coins as genuine examples. As I’ve never really handled them before and didn’t even imagine that an independent grading company could get caught out, I didn’t think to be more careful before deciding to “crack” the coin out of the slab.

We’ve since written off the cost of our lack of knowledge, but I thought you’d like to see images of our coin against a genuine example, so you don’t befall the same fate. Be advised that the comments below are only between the counterfeit coin and a genuine example from one particular pair of dies. Pridmore shows that three different varieties exist, this is confirmed when checking images of a number of different genuine coins online, so the below comments shouldn’t be taken as being definitive.

Obverse - Counterfeit of the British East India Company (Madras) 1808 Gold Pagoda

Compare the above images against each other, and you can see a number of distinct differences:

- The pellets around the rim of the coin are much more numerous than on a genuine example (75 as opposed to 46);

- There is a stop between the “A” in “PAGODA” and the Persian letter to the right of it;

- Each of the stars appears to have a flat pellet at the centre, this isn’t seen on genuine examples; and

- There are numerous differences in the scrollwork below the base of the pagoda.

Reverse - Counterfeit of the British East India Company (Madras) 1808 Gold Pagoda

Compare the above images against each other, and you can see a number of distinct differences on this side also:

- The pellets around the rim of the coin are much more numerous than on a genuine example (77 as opposed to 54);

- The star at the top of the coin also looks to have a flat pellet at the centre, this isn’t seen on genuine examples;

- The number of pellets in the fields surrounding the central figure (Vishnu) are completely different;

- Vishnu’s crown is quite different when compared to the genuine example; and

- The Tamil character on the right hand side at about 3 o’clock is quite different to the genuine one.

All in all, this has been a great lesson for us to learn (again) - it pays to be educated in our areas of numismatic interest.

One excellent source of information on these coins was this posting in a popular online numismatic forum, click this link to read more.

Comments (1)

Thanks

By: Ken Heffernan on 15 November 2021Many thanks Sterling and Currency for sharing this lesson. I appreciate your professional contribution that will help keep the numismatic community of Australia attuned to these pitfalls. I prefer to see a coin well conserved but out of a slab, but had expected that slabbed coins would at least assure genuine status. Ken