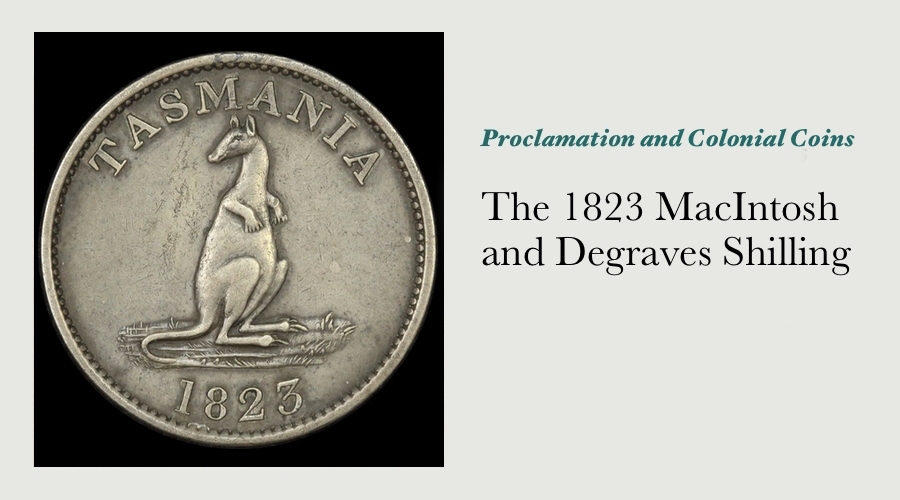

The 1823 MacIntosh and Degraves Shilling

The Macintosh and Degraves silver shilling is the first tradesmans' token manufactured for use in Australia, and as the only shilling token issued by any Australian merchant it is also the largest denomination in the entire token series. This token is in fact the first item of Australian decorative art to feature the term Tasmania, and the fourth (possibly the third) record of the term Tasmania in any medium. The token also shows the earliest depiction of a kangaroo on an item of decorative art available for private ownership, and is one of less than two dozen extant items of silver produced prior to 1821 and with an Australian history.

Peter Degraves is regarded as being a highly influential figure in Tasmania's colonial economy, the Cascade brewery that he founded is still active and successful today. The exact reasons behind the production of this token are not known, however it is possible that Degraves saw it as being not only a means of raising the profile of his new commercial enterprise in Tasmania, but also as the first phase in a strategy to remedy problems with Tasmania's circulating coinage. These tokens were never issued for circulation, yet it is believed that approximately fifty examples are with collectors around the nation. Just what happened to the balance of the original mintage remains a question to this day.

Journey of Enterprise

The “Cascade Saw Mills” was a venture planned by Peter Degraves and his brother-in-law, (Major) Hugh McIntosh. Degraves was the son of a highly respected doctor, and had married McIntosh's sister, Sophia. McIntosh had retired following many years service with the British East India Company, his final posting was seven years with the Persian Royal Court. Degraves had somehow determined (possibly through correspondence with contacts already in Tasmania) that there was strong demand for sawn timber used in construction there. After completing his studies in civil engineering in 1821, he resolved at the age of 44 to emigrate with his wife and eight children. It has been asserted that Degraves' decision may have been at least partly motivated by the loss of a significant sum in a business transactioni.

Degraves' partnership with MacIntosh is one of only two formal commercial relationships recorded for him during his entire time in Tasmania. Despite MacIntosh being older by two years, Degraves was clearly the more dynamic partner, and it is quite possible that the pair silently joined MacIntosh's retirement funds with Degraves' energy to their mutual benefit. There are no records of MacIntosh participating in the sawmills or any other areas of the Degraves' “empire” in any significant way.

It is not known exactly when the MacIntosh & Degraves tokens were produced, but given the manner in which events unfolded between the date of Degraves' decision to emigrate and the date of his eventual arrival in Tasmania, it is most likely that they were conceived and struck before October 1821.

Not content to merely travel to the other side of the world and make their fortune following their arrival, the entrepreneurial partners purchased a vessel to earn a profit from their voyage to boot. A barque named Hope was acquired to not only carry their families and machinery to Tasmania, as well as a group of paying passengers. Their fellow passengers were Wesleyan Methodists, who wished to settle in Tasmania “to relieve the moral destitution of the colonists who were living in a state of ignorance, misery and sinii” - the Hope set sail in October 1821.

Unfortunately for MacIntosh & Degraves, their voyage to Tasmania was nothing short of a complete disaster. The ship encountered a large storm while still in the English Channel, and was so severely damaged that it was forced to return to port. The ship was even further damaged “by careless handling on the part of the Harbour Masteriii”, and insurers became involved. Repairs took far longer than a prompt departure required, and as a result, a group of disgruntled passengers “secretly and artfullyiv” took legal action against MacIntosh & Degraves.

It was common practice in that era for paying passengers to pay for half of their voyage prior to departure; half upon arrival and to supply their own provisions for the journey. The Hope's intended departure date was August 20th 1821 – it did not actually leave until two months later, so a quarter of the passengers' provisions would have been exhausted before the ship had even left. The extended delays to repairs meant that the supplies were fully exhausted before the Hope was seaworthy again. While it was entirely usual for passengers to sustain themselves during any delays, the Hope's passengers were facing the prospect of being forced to fund supplies for at least an extra eight months – twice the budgeted amount, yet without any immediate propsect of departure.

It is little wonder then that a core group of less scrupulous passengers agitated strongly to remedy the situation, albeit in a less than virtuous way for a group “dedicated to relieving moral destitution”.

Their objective was apparently to have the Hope siezed and scrapped, which would in turn enable them to obtain a full refund on their passage and free travel to Van Diemen's Land in a government ship.

Due to the volume and colourful nature of the claims made by the passengers, the Lords of the Treasury recommended that MacIntosh & Degraves be penalized in order to fund “...the expenses of conveying those 'deluded' passengers to their place of destination in another shipv.” MacIntosh & Degraves were arrested and the Hope and its cargo was siezedvi. It is possible that that it was at this point that the vast majority of the MacIntosh & Degraves tokens were melted by the exchequer.

MacIntosh & Degraves felt the claims against them were entirely unwarranted, and in turn threatened to bring an action against harbour officials for their negligence in handling the Hope. In the course of an investigation relating to this action, the Hope's passengers were questioned under oath by the Lords of the Treasury. Alarmingly, their claims against MacIntosh & Degraves were apparently far less sensational than when they were first presented. The Hope's passengers were eventually given transit to Van Diemen's Land in an old convict vessel named the Heroinevii, and may have been accompanied on this voyage by Major MacIntosh.

As part of the settlement to these intertwined cases, Degraves was able to obtain government funding to subsidise the expenses of relocating the sawmill to Van Diemen's Land; six months free rations for his family; as well as the services of a blacksmith & three convict carpenters to assist with the establishment of the sawmillviii.

The Saw Mills In Full Operation

Unfortunately for Degraves however, while both of these lawsuits were underway, he was also sued by the previous owner/s of the Hope. The nature of this lawsuit is not yet widely known, however as the plaintiffs were awarded £2,000ix, it is believed to be the probable cause of Degraves' arrest in 1826.

These three lawsuits obviously took quite some time to draw to a conclusion, and so Degraves did not actually depart England again with a new group of passengers until September 19th 1823. The Hope did not arrive in Hobart until April 18th, 1824.

Immediately upon arriving in Tasmania, the partners applied to the Lieutenant Governor for a grant of land. Degraves was granted 200 acres at the Cascades on 11th June 1824, and an announcement was made on August 13th 1824 that the Cascade Saw Mills were fully operationalx.

In May of 1826, Degraves was spotted by a Francis Court (or Count); the licensee of the enticingly named Help-Me-Through-the-World Inn in Collins Street (Hobart). Court was aware that Degraves still had debt outstanding in England, and notified the colonial authorities. It seems reasonable to speculate that Mr Court was in all probability related to the £2,000 settlement in May of 1823, and had become aware that Degrave's new venture was successful. Either way, Court was somehow known to the previous owners of the Hope.

The result of this suit was that a bill of sale was placed on Degraves' house; sawmill; machinery and timber in August of 1826. The Insolvency Act had apparently been amended in the years between the date the debt in question was incurred and the commencement of Degraves' trial in Hobart, and although the amended Act seemed to indicate that the partners had fulfilled their obligations to the plaintiffs, the Chief Justice ruled otherwise. The sale of the partners' assets was stayed, however MacIntosh & Degraves chose to dissolve their corporate relationship in October of 1826. Degraves was sent to Hobart Gaol, and control over the Cascade Sawmills was handed to Mr Court, perhaps with the intention that he would operate it until the £2,000 in debt had been repaid.

It is known that Degraves attempted to negotiate with his creditors regarding the operation of his sawmill – he agreed to repay the debts attributed to him “stating that he was not indebted by one shilling in 1822xi.” Such a reference to the exact denomination used on his token shortly following the period that it is thought they were struck is probably nothing more than happenstance, however it is a tantalizing possibility that Degraves was using this negotiation gambit to protect his assets in some way - if we could determine that the assets he wished to protect were his hoard of tokens, it would have significant implications for our understanding of their distribution.

Degraves' energies were not at all drained by his imprisonment - he frequently petitioned Lieutenant Governor George Arthur for his release, and was eventually granted his freedom by Arthur in 1831.

The Beginning of an Empire

Degraves put his entrepreneurial drive into gear as soon as he was released - in 1832 he founded the now famous Cascade brewery. Cascade's beer steadily rose in popularity to become Tasmania's premier beer by the 1850's - no mean feat at a time when there were at least 40 other breweries in competition. A second sawmill; a flour-mill and bakehouses were built in the years following - with his sawn timber, flour, bread and biscuits, the Degraves “empire” was said to earn close to £100,000 a yearxii.

In the years following the establishment of his brewery, Degraves played a significant role in public water policy in Tasmaniaxiii; played a key role in the establishment and design of the Theatre Royalxiv (to this day considered one of the best theatres in Australia for acoustics) and operated a shipyard between 1841 and 1851.

Major Hugh McIntosh died December 24th, 1834, as a beneficary in his will. Degraves gained ownership of 3,200 acres of land on Mount Wellington. Degraves' wife Sophia passed away at the age of 50 on May 30th 1842.

Degraves caused a public outcry when he temporarily cut off the town's water in 1845, further public complaints were made regarding poor water quality in 1846xv. His contract to supply Hobart Town with clean water was eventually broken by the Colonial Government, and the responsibility was handed over to a Major Cotton. Degraves' subsequent claim in 1848 against the Public Works Department was countered by a public petition. Feeling within Hobart Town ran high, and a Mr H. Moore, the editor of the Hobart Town Guardian newspaper, apparently ridiculed Degraves in public. Degraves (at the tender age of 70) apparently threatened to assault Moore, who pressed charges. Degraves refused to post bail over the matter, and was imprisonedxvi. Although he was released first thing the next morning, this incident further demonstrates the determination of Degraves to pursue what he felt was right, regardless of the consequences.

Peter Degraves died at Hobart on December 31st 1852, and is described by the Australian Dictionary of Biography as being “...typical of those practical men who were essential for the building of new colonial economies. In spite of obstacles, checks and frustrations which daunt men of lesser purpose, he pursued his self-ordained tasks with that energy which flows from dedication and ambitionxvii.”

A book on the history of the Cascade Brewery describes it as being “a small but viable and ambitious player in the world of brewing, and a company of considerable economic importance to Tasmania. It is also a unique part of Australia’s industrial heritage and a fitting memorial to the courage and foresight of Peter Degravesxviii.”

From Possibly 2,000 Struck in 1821 to Perhaps Just 50 Today

Primary evidence of a mintage figure for the MacIntosh & Degraves shilling token has never been found, however for quite some time it has been presumed that 2,000 is a reasonable estimate. In 1957, the noted South Australian numismatist James Hunt Deacon stated that “one authority (Reynolds) gives the [mintage] figure at £1,000 worthxix.” Hunt Deacon's comments on the topic show that he was fairly confident in the source of this estimate - at this stage no alternative figures have been proposed.

It is widely assumed that “there are much less than fifty [MacIntosh & Degraves tokens] surviving todayxx” , however research indicates that only around 21 individual tokens have been tracked through auction in Australia since 1975. In addition to these sighted at auction, there are no less than seven examples in the famed Dixson collection (housed in the State Library of NSW), possibly others in public collections around Australia, and of course others that have changed hands through private treaty.

If 2,000 tokens were produced, and they were not issued for circulation, how then is the apparent loss of almost the entire mintage explained?

If Degraves did have all or even a significant quantity of his tokens in his posession by the time he reached Tasmania in 1824, it is difficult to believe that an entrepreneur as energetic as he would have witheld them until his death in 1852. This period of nearly three decades is marked as a time when specie was in chronic shortagexxi, yet there has never been the slightest indication that the tokens were issued.

Hunt Deacon believed that if “the supply [of shilling tokens] was ready at the time of the [Hope's] departure from England of the partners, this with the exception of perhaps a few specimens, could have been siezed with the other goods and cargo when the ship Hope was arrested and not handed back on the release of the shipxxii.”

The Historical Records of Australia show that the Hope and it's cargo was siezed on May 18th1822xxiii, and further that the court in England had instructed that Degraves “be exchequered” so that the penalties imposed could be paid. To the dispassionate customs officials that siezed the Hope, the tokens would have appeared to be nothing more than bullion waiting to be melted down. Easily sold for their silver value, the silver tokens may have indeed been one of the first items of cargo to be sold.

Furthermore, the total (presumed) Sterling value of the tokens was equal to half the sum Degraves was found in 1826 to owe the previous owners of the Hope. Even though he was a determined and headstrong individual, it is extremely unlikely that he would have endured two stints in debtor's prison (the first a term for 12 months, the second for five years); forced his commercial partnership with MacIntosh into insolvency; allowed his family home to be sold and accepted his wife being forced to seek paid employment, when he had ready access to half the sum required to satisfy his debtors. If Degraves had access to his tokens when he was jailed in 1826, he would surely have scrapped them in order to meet his debts.

Alternative hypothetical explanations of the extreme rarity of these tokens could be that they were lost (perhaps during the storm while the Hope was in the English Channel), perhaps stolen or even willingly disposed of by the partners at some point. As there was no record of the Hope losing cargo when it encountered the storm in the English Channel; no article in any Hobart newspaper notifying the Tasmanian colonists of the theft of £1,000 in silver or anecdotal stories of the tokens being scrapped in Tasmania, the most logical explanation is that the vast majority were siezed by authorities in May 1822. Those with collectors today would surely have been included in the partners' personal effects.

Technology & Enterprise – A Solution to Tasmania's Currency Woes

Several numismatists have thought it reasonable to presume that Degraves had more to do with the conception and production of the shilling token than MacIntosh, and that the tokens were struck at Boulton's Soho Mintxxiv. Thse sequence of known events appears to indicate that the tokens were struck prior to October 1821 at the Soho Mint.

Early on in his education, Degraves was apprenticed to the noted Scottish civil engineer John Rennie, a man described by the BBC as being “one of the greatest engineers of his agexxv” and best known for his work designing the London bridgexxvi. Rennie was a contemporary and friend of James Watt and Matthew Boulton – two men at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution and whose steam engines revolutionized the way numerous industries operated, not least the manufacture of coinage. Not only did their technological advances generate profits for their commercial enterprise, they improved social and cultural conditions around the world as well.

James Watt died in 1819 aged 83 and Matthew Boulton died in 1809 aged 81, so Degraves may not have forged a relationship with either of those men directly. When the commercial partnership between Watt and Boulton expired in 1800 however, it was transferred to their sons – James Watt Junior and Matthew R. Boulton. It has been asserted several times that Degraves was personal friends with both these menxxvii (perhaps he encountered them when he was serving his apprenticeship with Rennie) If this is correct, it may support the assertion that the Soho Mint produced the MacIntosh & Degraves tokens.

With the introduction of his sawmill and the associated engineering to Tasmania, Degraves was also bringing new technology to an industry constrained by the limitations of manual labour – obviously on a far smaller scale but not entirely unlike the efforts of Boulton; Watt and Rennie some years before him.

Degraves must have been aware of the problems colonists in Van Diemen's Land were experiencing with circulating coinage, and he may have seen his shilling tokens as the leading edge of a strategy to improve commercial conditions in Tasmania through a blend of technology and private enterprise. Evidence of this intention is a comment in Goodwin's “Emigrant's Guide to Van Diemen's Land” of 1823 that MacIntosh & Degraves intended to “...issue sixpenny, shilling and halfcrown tokens...xxviii”

Degraves was clearly a man of enterprise and determination – he ventured to the other side of the world to make his fortune; vigorously defended himself against charges relating to the Hope; engineered not only the sawmill itself but also it's relationship with its surrounding land; unceasingly lobbied the Lieutenant Governor for his release from gaol; pursued a range of commercial ventures once he regained his freedom and was a patron of the arts through the foundation of the Theatre Royal. It isn't unreasonable to presume that Degraves saw his shilling token not only as one means of increasing the profile of his commercial enterprise, but also as an effort to emulate his mentors and remedy the range of economic and social ills evident in Tasmania as a result of the absence of regular supplies of circulating coinage.

Why Weren't These Tokens Issued?

A dire need for silver and copper coinage in Tasmania certainly remained for much of the 19th century, so why then didn't Degraves proceed with his intention of issuing his tokens?

If we accept the premise that the shilling tokens were most likely siezed by English customs authorities in May 1822, we have a perfectly good explanation as to why the tokens were not issued – they did not exist. If Degraves believed the strategy had merit however, there would have been nothing to stop him from ordering more tokens from the Soho Mint or elsewhere.

During the 1820's, the colonial governors of Tasmania and New South Wales re-rated the Sterling value of Spanish dollars several times, by as much as 20% on each occasion and with immediate effect. Colonial records also confirm that, independent of these changes, Spanish dollars arrived in their tens of thousands on at least four occasions between 1823 and 1848xxix – these large increases in the supply of silver specie also had a significant short-term effect on the values at which local merchants would accept them in trade. Degraves was certainly an entrepreneur and no stranger to risk, however this level of volatility may have been too high for him to see the commerical value in taking any possible notion of reforming Tasmania's specie seriously.

How Were the Remaining 50 Tokens Distributed?

It is widely acknowledged that there is no way the tokens could have been distributed in 1823 - Degraves was in gaol in Britain for most of that year, and the partners did not even arrive in Tasmania until April 1824xxx. Once the sawmills had become operational by August 1824, It was probably Degraves' intention to issue his tokens in trade and to have them advertise his business, however they could only have remedied the lack of specie in the colony (another of his likely objectives) if they were issued in significant quantities. It is likely that a man of Degraves' character would have preferred to personally keep any remaining tokens not siezed by the British port authorities, rather than to issue them in trade. Most examples extant are in Very Fine or better condition, and as we know from even a cursory examination of the population of any of the other Australian silver tokens, this is far, far less wear than would be seen if they were issued for circulation.

Degraves could have gifted the tokens throughout his life as mementoes - he would have been 71 years of age in 1849, and presumably in a reflective mood on the 25th anniversary of his arrival in Tasmania, he could very well have benevolently gifted a small number of them at this time to family members, trusted colleagues and customers. If Degraves did not distribute them during his lifetime, it is likely they were discovered within his personal effects following his death, and that they have made their way into the collector market through various generations of the Degraves family. There is a record in the Royal Numismatic Society's Numismatic Chronicle that one had been purchased from a dealer in London in 1848xxxi, this could indicate that at least some had been distributed prior to Degraves' death in 1852, or that some were illicitly saved from the Exchequer's melting pot in 1822.

Better understanding of the distribution of these tokens will be gained by studying the provenances of those available to collectors, where these details are known.

Van Diemen's Land – More Properly Known as Tasmania

Hunt Deacon makes brief mention regarding the relevance of the name Tasmania on the reverse of the MacIntosh & Degraves token. He raised the theory that some considered this name was not widely in use around 1823, and that it could be possible that the tokens were not produced until much later than the date stamped on the reverse might indicate. A past curator of the British Museum's Coin & Medal Department is also known to have raised this concern – notes on the registration record of the MacIntosh & Degraves shilling held by that organization include “I suspect this coin, because in 1823 the island was called Van Diemen's Land1.”

An examination of the facts surrounding the transition in names between Vand Diemen's Land and Tasmania show that this concern may be misplaced.

The coast of Van Diemen's Land was first sighted by the Dutch navigator Abel Tasman on November 24th 1642, and was first circumnavigated by George Bass & Mathew Flinders in 1798. The first British settlement in Van Diemen's Land was confirmed between March and May in 1803 - 49 people were resident there in September 1803, 469 by February 18052. Governor Gidley King had five primary reasons for establishing a settlement on Van Diemen's Land:

-

- To ensure that the French could not settle there;

-

To foil any imperial designs in South East Australia;

-

To “farm” the timber that was known to be plentiful there;

-

As a gaol for convicts transported from the United Kingdom;

- As a “haven” for free settlers.

Although the early years of settlement at Tasmania were dominated by the presence of convicts, there was a significant number of free settlers resident there also. These free settlers were proud of their achievements and their adopted homeland, and did not want it to be “stained” by an association with convicts. For this reason, there was a popular, informal and almost underground movement that advocated the adoption of the name “Tasmania” for the island first known as Van Diemen's Land.

Written evidence of this preference for the name Tasmania can be seen littered throughout private correspondence between Tasmania, New South Wales and the United Kingdom. Ample, more public evidence of the popular push for the term Tasmania can be seen well before the official change in 1855:

-

- A map of the world issued by Laurie and Whittle in 18083. This is widely believed to be the first written reference to the name Tasmania.

-

The naming of a bush by the botanist Robert Brown as Tasmannia Winteraceae in 18144. This was published in an appendix to Mathew Flinders' Voyage to Terra Australis. The bush is now known as “Mountain Pepper”.

-

The publication of “Godwin's Emigrant's Guide To Van Diemen's Land, more properly called Tasmania” in 1823. This guide was purchased by British emigrants considering Tasmania, and is believed to be “the first use of the term Tasmania in a stand alone publication.5” An earlier version of this guide was published in 1821, although it is not yet known if it had the same title.

The term Tasmania was littered through the press of the 1820's; 1830's & 1840's on the island, it was also used well before 1855 when popularly organized social, cultural and religious organizations were formed. Several examples follow:

1826 - The Tasmanian Turf Club was established;

1828 – The Tasmanian Lodge of Freemansons was established;

1839 – The Tasmanian Regatta was inaugurated;

1841 – Bishophoric of Tasmania was created;

1843 – The Tasmanian Literary Journal appears for the first time.

In addition to all of the above evidence, it is known that the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli used the term Tasmania in private correspondence with Sir John Franklin in February 18416.

That the MacIntosh & Degraves shilling features the name Tasmania as part of it's reverse design does not give cause to presume that the token was produced around the time of the formal push towards the adoption of the name Tasmania (between 1853 and 1855), lends weight to the theory that the tokens were produced before October 1821, and serves to emphasize the token's status as an important piece of colonial Australiana.

The MacIntosh & Degraves shilling is in fact the first item of Australian decorative art to feature the term “Tasmania”, and the fourth (possibly the third) record of the term Tasmania in any medium.

The manufacture of these tokens predates Godwin's text, even in late 1822. It is interesting that a non-colonial would use the term so early in the phase during which the name of Van Diemen's Land evolved to become Tasmania. Speculation on the use of the term by Degraves could be that his choice was entirely utilitarian – to maximize the possbility that the tokens were accepted by the local population. It is quite probable that Degraves came to be aware of the term through correspondence with private colonists in Tasmania early in his planning process. This provides further evidence of Degraves' extensive planning of the trip – it is probable that information on the potential of a lumber industry was conveyed to Degraves by the same free settler.

Kangaroos After Stubbs

The style of the kangaroo on the reverse of the MacIntosh & Degraves token also enables an informed decision as to when these tokens were designed and manufactured. Anyone familiar with the anatomy of a kangaroo will be easily able to discern that the animal featured on the MacIntosh & Degraves token is different in a number of ways to reality. The animal on the token has the following characteristics:

The ears and snout are more like a dog than a kangaroo;

-

The shoulders appear small and rounded - with limited strength and flexibility;

-

The hind legs are almost like those of a largely sedentary animal.

Published research indicates that all of these characteristics are common to the way in which kangaroos were depicted in Britain in the early 19th century. Travel by artists from Britain to Australia was obviously quite limited in the early 1800's, and so most artists looking to depict a kangaroo were forced to work from earlier depictions by other artists.

George Stubbs was a British artist active at the turn of the 19th century, most famous for his energetic portrayal of horses. Although Stubbs was the first artist to paint a kangaroo, he was not able to actually work from a living animal – some time in 1771 or 1772, Sir Joseph Banks had commissioned him to work from a skin brought back with the Endeavour. Largely as a result of the subject material available, the Kangaroo rendered by Stubbs was not entirely true to life. An engraving of Stubbs' painting was featured in Hawkesworth's “Voyages in the Southern Hemisphere”, this image was “the first accessible pictorial representation of the animal which so amazed and intrigued Europexxxii.” Depictions of kangaroos in paintings and decorative art in the early 19th century are often described as being “in the style of Stubbs”, or similarly.

In his work entitled “The Kangaroo in the Decorative Arts”, Terence Lane notes that the kangaroo on the MacIntosh & Degraves token as being “a Stubbs / Hawthorn kangaroo7.”

Lane further states that “Few objects bearing the kangaroo motif have survived from the 1820'sxxxiii.” The first known depictions of kangaroos in Australian decorative art are:

-

1808 – The “Davison” snuff box. Presented by a Walter Stevenson to his father.

-

1821 – Chairs produced for (NSW) Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

Colonial Australian Silverware and the Degraves Token

Silver is one of the main media used by artisans and craftsmen in colonial Australia. It appeals to collectors today due to its status as a luxury good; its function in the daily life of colonial Australia; is function as a store of value and as an heirloom.

Alexander Dick arrived on October 16th, 1824 - “few people capable of making simple objects in silver had arrived in NSW8” by this time. With the growth of the colony, and the resulting “improvement in standard of living and expansion of the population base, a much more solidly based mercantile community emerged9.” It was noted that“bullion was in short supply in 182910.”

| 1.” | |||

|

Ferdinand Meurant |

1808 |

- |

Gold mounted snuff box (Stevenson). “One of the earliest surviving [silver] objects with an Australian history2” Presumably of English manufacture, held in a private collection. |

|

|

1819 |

- |

A trophy for a racing event, not produced locally and not extant.“The first piece of raised silver relating to the colony of NSW3.” |

|

Jacob Josephson |

3.1.1818 |

6.12.1845 |

Nothing known |

|

Walter Harley |

August 1813 |

1822 |

Shoe buckle “one of the earliest known items of NSW silver4”; sauce ladles; teaspoons - held in private hands5; pap boat |

|

Samuel Clayton |

1.4.1817 |

1835 |

Printing plates for the Bank of NSW and the Bank of Australia (date unknown)6; 2 presentation trowels; teaspoon; Halloran medals (produced at the request of a school principal, for presentation to benefacors of the school)7. At least one of these is in private hands. These medals are dated 1819; 1822; 1823; 1823 and 1824. |

|

Ferdinand Meurant |

|

26.5.1806 |

Ferdinand Meurant |

|

James Grove |

|

|

Pepper castor, it is enscribed as being “The First Piece of Plate made in Van Diemen's Land; AD 18058.” Grove is described as being “Australia's First Silversmith9”. |

|

David Barclay |

June 1830 |

? |

? |

|

James Robertson |

7.1.1822 |

1830 |

Parramatta Cup; shop regulator |

|

James Oatley |

27.1.1815 |

|

“Throsby Park Timekeeper”, and several longcase clocks “in limited numbers10.” |

|

Alexander Dick |

14.4.1826 |

|

A significant quantity of Alexander Dick's work in silver remains available to private collectors. |

Publicly Owned Australian Colonial Silverware (Pre 1821)

1788 Foundation plaque for Government House (Mitchell Library)

1804 Pocket compass by John Austin (Mitchell Library)

1808 Gold mounted snuff box for Walter Davison (Powerhouse Museum)

1818 – 1820 Pap boat by Walter Harley (Powerhouse Museum)

1820 Sauce ladles by Walter Harley (Powerhouse Museum)

Auctioned by Goodmans: lot 323, 1-5/7/2006?

1823 Presentation Trowel by Samuel Clayton (Mitchell Library)

Australian Colonial Silverware (Pre 1821) – Uncertain if Publicly or Privately Held

1819 - 1824 Halloran Medals (Four examples)

Privately Owned Australian Colonial Silverware (Pre 1821)

ca 1788 Charlotte Medals (Unique in silver)

1805 “Collins” pepper caster from Van Diemen's Land, by James Grove

1813 NSW Holey Dollars and Dumps, authorised by Governor Macquarie

1818-1820 Silver shoe buckle made by Walter Harley, retailed by Jacob Josephson

1819 “Halloran Medal” for Robert Campbell, by Samuel Clayton

c1820 Pair of “fiddle pattern” teaspoons by Walter Harley

1823 Macintosh & Degraves shilling tokens

1825 Fiddle Teaspoon by Samuel Clayton, for George Campbell

Other than the Holey Dollar and Dump, the Macintosh & Degraves shilling token is one of the earliest known items of silver with an Australian history. Just 20 items of Australian silver dated prior to 1821 are known to exist, only seven of these are available for private ownership.

One of the true rewards of owning and studying historic numismatic items is the pleasure obtained in contemplating a link with an individual or era that has played a formative role in economic history. Not only is the MacIntosh & Degraves shilling token highly rare; it is the first token manufactured for use in Australia; the largest denomination in the entire token series and has a reverse style that definitively dates it to the early 1800's. It remains a direct and personal link a key figure of Tasmania's colonial economy, one “typical of those practical men who were essential for the building of new colonial economiesxxxiv.”

A range of questions can be posed:

How did Godwin come to know of the existence of the tokens (and thus Degraves' plan to issue them)?

Were the tokens mentioned in the 1821 version of Godwin's text?

Did Thomas Kent have any association with Degraves?

Which map did / would Degraves have used on the voyage to Tasmania?

Who made the gold mounted snuff box? When and for whom?

Comments (1)

I have one of these tokens

By: Wade Duncan on 16 March 2024The token I have appears to be in very good condition. The protective sleve it is in says it is a 1825 token, however, on close inspection witha magnifying glass it is indeed a 1823.